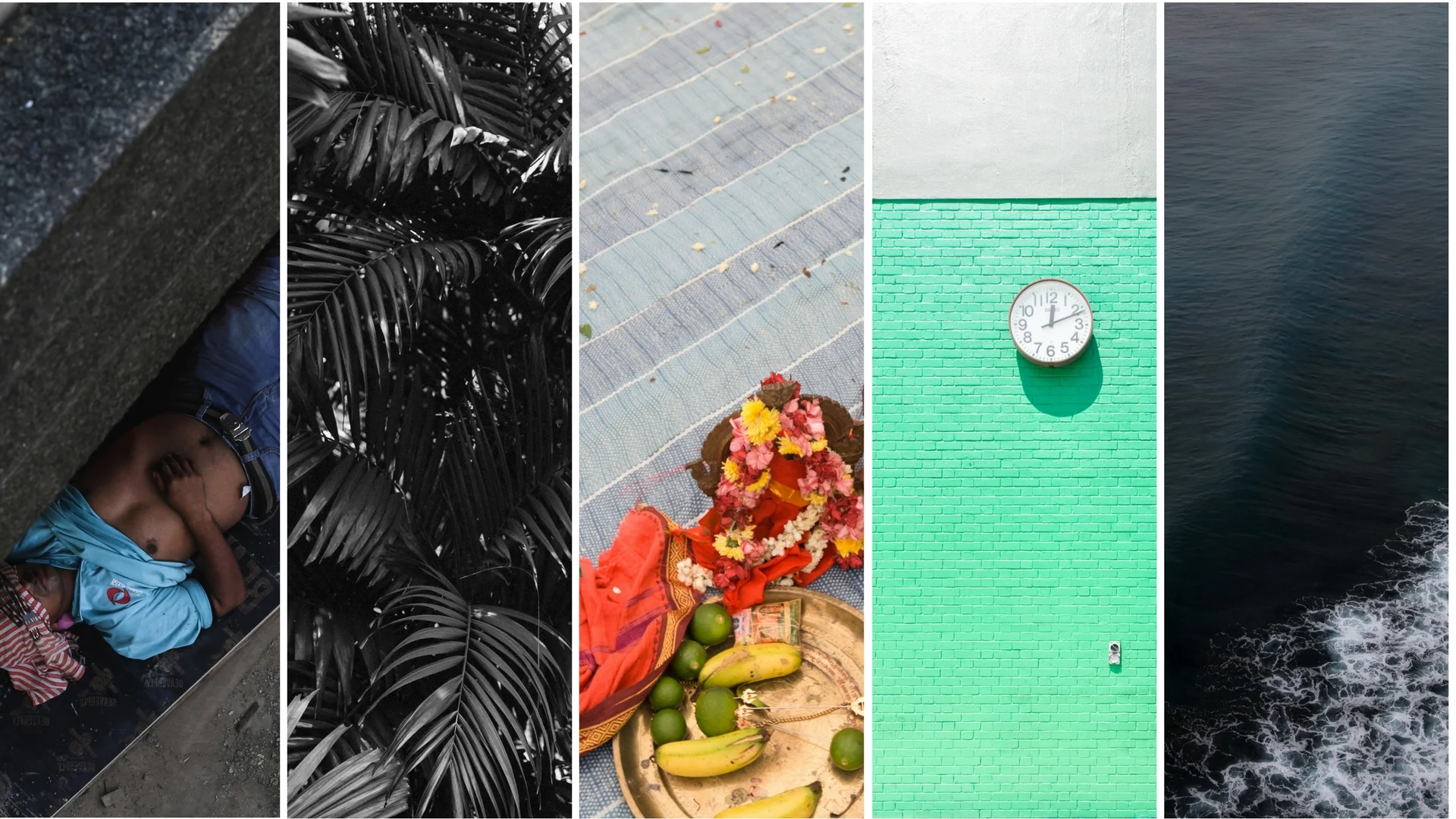

KONYAK : TIME WAITS FOR NO WARRIOR

These last remaining Konyak warriors are living time capsules to the past, whose stories chronicle tribal times fast-fading from the eyes of the world.

FEATURE Nº 21

The last generation of Konyak warriors, Lungwa village, Nagaland. Images: Justin Ong

A film by Sadiq Mansor

In the misty borderlands between India and Myanmar, The Konyak warriors are vanishing into the chronicles of history in this remote region of the world.

The Konyak are members of the Naga people who have lived in the verdant northern Indian state of Nagaland for hundreds of years, observing ancient rituals passed down through the generations.

They are most well-known and documented for their warrior headhunting practices, which for hundreds of years formed the spine of the tribe’s status, order and hierarchy.

In the past, the Konyak observed animism and worshipped all elements of the natural world, including plants, trees and natural phenomena, believing the living world itself to be a spiritual being.

Among the Konyak culture, honour has always been integral to tribal customs. Fierce battles and raids of neighbouring hillside and forested villages would end with victorious Konyak warriors returning home with enemies’ heads. In return, they would receive their reward of fresh ink and new tattoos on their face, neck, arms, legs and back. These symbols on the skin represented the warrior’s place within the tribe, their many battles and life’s journey.

At the turn of the 20th Century, worlds collided when Christian missionaries made contact with Konyak, spreading new ideas, ideologies and religion throughout the land.

Initial resistance soon turned to acceptance. Slowly, Christianity ebbed into daily life. Divinity changed. Gods changed. Buildings changed. Roofs grew spires and crosses looked down upon the Konyak land.

Like so many other indigenous populations around the world, soon Christianity was accepted as the new faith. Little did the tribe realise, this would spell the end for their long history of rituals.

Under British rule in 1935 headhunting was outlawed. While some continued under the radar, by the 1970s the practise had faded into the history books.

Today, almost all of the Konyak communities in the region known as Nagaland have converted to Christianity. Most villages have a church and Sunday services presided over by a pastor.

The elderly warriors’ tattoos fade with age and headhunting exists only in the words of recounted tales to the younger generations, anthropologists, filmmakers and journalists. There are also worn reminders in necklaces adorned with little bronze heads, which symbolise how many enemy skulls a Konyak warrior has collected. One means one, but two, three, four, five or more can mean many more real human heads.

The warriors’ children and now grandchildren wear modern clothes and go to church on Sundays. They cram into the small white chapel and sit elbow-to-elbow smartly dressed. They sing hymns. They pray. They smoke. They listen to the pastor's preaching from bibles. Sometimes the old warriors wander inside, too. Their heavily tattooed faces cut a sharp contrast to their pristine white collared shirts, like two different generations sitting in one pew, one body.

The Konyak story is a familiar one of worlds colliding. Where tribes and ancient rituals meet the modern world and generations pull away from remote roots to enter the human centres of civilisation, enticed by money and new religions.

These last remaining Konyak warriors are living time capsules to the past, whose stories chronicle tribal times fast-fading from the eyes of the world.

Words by Sadiq Mansor & Fraser Morton

Nagaland, northern India. Images: Justin Ong

TIGER RANGERS

The tiger had finished eating the ranger’s dinner, a meal of nasi goreng chicken and rice, and now beast and man crouched a few metres from each other their eyes locked.

On the trail of the critically endangered Sumatran tiger with the men fighting to save the species from extinction.

FEATURE Nº20

Ranger Hendra in the Leuser National Park.

The tiger had finished eating the ranger’s dinner, a meal of nasi goreng chicken and rice, and now beast and man crouched a few metres from each other their eyes locked.

The sun was sinking over the Sumatran jungle canopy. Hoots of Siamang black gibbon called out. Leeches rained down from branches and sucked blood through the ranger’s skin, which was goose-pimpled in fear.

The nearest village was a three-hour canoe journey down-river. The ranger’s last outpost, a log cabin, was a 10-mile hike away. There was no phone signal, not that it would have mattered.

The tiger licked a paw and purred like a giant housecat. The ranger did as he always instructed his team to do in this situation: “You freeze. You don’t move. You wait.”

Thirty minutes passed. The ranger knew it was time to act, so he decided to negotiate with the tiger.

“Excuse me Grandma, nenek,” the ranger whispered at the tiger. “We love you, but you are in our path. Would it be okay if we can pass you, please, terimah kasih? We gave you all our food.”

The tiger seemed indifferent to the question.

The ranger, a former Aceh rebel fighter turned conservationist named Hendra, along with his two deputies, began to inch away from the tiger and back down the path from which they came.

They crept in the darkness for a few hundred metres, where they found their earlier campsite, pitched their tent, zipped themselves inside their sleeping bags and breathed a sigh of relief, “Terimah kasih Grandma, thank you,” Hendra said aloud.

Ranger Hendra sets a camera trap fitted with a motion sensor to capture tigers in the Leuser National Park.

At about midnight one of the two younger rangers had to pee. As he began to relieve himself stood in the tent entrance, the deep rumbling yawn of the tiger jolted him. It was so close he could feel the animal’s warmth. The tiger lazed unbothered in the leaves a few metres away. The ranger slipped silently back into his tent and zipped the flimsy door shut. As he listened to the leaves rustle and the tiger breathing, after a while his fear made way for tiredness and he and the other rangers fell asleep.

The next morning they awoke, made their breakfast of nasi goreng, packed up their tent and began their hike into the jungle, pausing as they passed the spot where they encountered the tiger the previous night. Then they pressed on to embark on their 15-day footpatrol of the Leuser National Park, on a mission to find animal poachers and illegal loggers as they defend the final habitat of the Sumatran tiger, the most critically endangered subspecies of tiger in the world.

“The tiger, nenek grandma, knows we are here to protect her. She will not kill us,” Hendra said, as he finished telling his story to our group after dinner at the remote Ranger’s Outpost, a few miles from where his encounter took place.

The origin of the name “nenek grandma” is simple: “The tiger is an old soul in this land and must be respected,” Hendra said.

That night I fell asleep in my bunk bed with sounds of the jungle and Hendra’s story buzzing between my ears. The next morning we would join the footpatrol and film the rangers as they perform their job, protecting the last of the tigers they call grandma.

ON THE TRAIL

I was trying not to think about the tiger story as we left the ranger hut and entered the trail the next morning.

Hendra marched in front, a machete dangling at his side, a cowboy hat on his head and dressed in a khaki safari suit embossed with the words Wildlife Protection Team Ranger in yellow on his chest and back. Next in line was Dedi, the Team Co-ordinator of the Forum Konservasi Leuser (FKL), who was in charge of the Wildlife Protection Team and 25 other ranger teams dotted throughout the 950,000 hectare jungle.

Hendra and Dedi moved along the trail methodically, scanning the trees ahead, searching the ground for tell-tale signs of poachers. Behind me I could hear the rest of our crew: producer, fixer, camera assistant, sound, and two other rangers.

The riverside trail we walked along was used by all the major animals, known as megafauna: elephants, rhinos, orangutans and tigers. All are listed as critically endangered in this last habitat on Earth where these species live together.

With each snap of a branch or squelch of mud I was sure would be followed by the unmistakable rumble of a Sumatran tiger alerted to our presence. An electric charge of adrenalin hung in the air as we ventured deeper into the jungle.

After an hour’s hike we saw no animals, only leeches, plucked from our bloodied skin.

Before we left the ranger station that morning there was talk that we might get “very lucky and see a tiger”. But as time passed the adrenalin subsided and the details of the jungle came into focus: Rushing water, distant gibbon hoots, swaying of trees, the high-pitched echo of cicadas, the croak of frogs.

We lugged our camera gear up hills, down slopes, edged across rivers, climbed behind waterfalls, hauled, hacked, slipped, slid and stumbled our way through the dense undergrowth. We were at the mercy of the jungle and our bodies proved feeble and unworthy.

Canoe boats are the only means to reach the ranger station.

Rangers Hendra and Fendi.

We were drenched in sweat, bloodied from scrapes that appeared from nowhere. We plundered on. Our destination was a set of elephant bones located somewhere on a ridge about another hour’s hike. The bones belonged to an elephant that had died in horrific pain from a wound sustained through a poacher’s trap.

A ranger holds a poacher’s snare trap used to capture tigers.

WAY OF THE POACHER

We learned about the poachers and their many ways to kill and maim. Their elephant traps were simple and medieval: a heavy wooden plate hammered with dozens of nine-inch nails pointing upward, concealed under leaves on well-trodden animal trails. The elephant stepped on the trap, bringing its four-tonne weight down on the nails.

In agony the elephant limped on until infection set in and eventually was left by its herd to die alone suffering. Only then would the poachers pounce and dismember the animal. No part of the massive beast was wasted. And this was true also for other megafauna sold in the illegal wildlife trade, including the most prized, the Sumatran tiger.

As little as 100 years ago, 100,000 wild tigers roamed Asia, but today across the continent a mere 3,900 remain. The Sumatran subspecies is listed as “critically endangered” with 400 left in the Leuser ecosystem.

They are on the brink of extinction due to habitat loss, lack of prey due to overhunting, human-tiger conflict, and the primary threat: poaching. Hunting is their single greatest threat.

Every inch of the tiger is sold in China, from the skins, bones, teeth, organs. They are seen as status symbols of wealth and traded on black markets flaunted as medicines.

The poacher gangs, which are orchestrated from China with local contacts in Sumatra, have gone to enormous lengths to catch tigers, which means the rangers in return have to go to extraordinary lengths to stop them. Both sides win battles, but the poachers are winning the war.

Gangs of poachers enter the jungle and don’t emerge until they have a tiger. They can spend days and nights hunting. Their weapon of choice is a snare trap.

This consists of tying a sharp wire and rope into a noose to the end of a bamboo branch which is bent and wedged between sticks hidden from sight by dried leaves. To the naked eye it’s impossible to see the traps, which are placed on trails just like the one that we find ourselves walking along.

The tiger steps in the trap, the spring shuts on the paw. Over days the distressed tiger tries to free itself, causing the wire to grind through fur and flesh until infection sets in.

Poachers snare traps used to catch tigers.

Ranger Adi.

Like the trapped elephant, the tiger dies an excruciatingly long death, with minimal wounds, so the maximum amount of animal can be sold.

We continued our walk along the tiger trail looking for poacher’s traps. We found nothing.

“The number of traps is decreasing, “ Hendra later told us. “In 2015 and 2016 we found hundreds. But since then the number has decreased because of our work.”

After an hour Hendra stopped in his tracks and raised his fist. Dedi stopped. I stopped, everyone stopped. After a few seconds, he moved forward, taking extra care with each step. A few metres ahead he bent down next to a thin bamboo branch seemingly growing straight out of the ground. He had found a tiger trap.

I focused the camera on him, as he grabbed a nearby stick and plunged it into a pile of leaves. There was a violent jolt, a whip of bamboo and spray of leaves and mud into the air, which settled after a few seconds to reveal Hendra holding a stick with the end frayed and caught in a wire-rope sling.

The team huddled around. They took photos, documented the co-ordinates with military precision, after which Hendra coiled the rope and wire and placed into a sac, which he put into his backpack. Another tiger trap had been foiled, and another tiger would live. One less to extinction.

Ranger Fajri.

A SHRINKING REALM

Sumatra was once known as the emerald of the equator, but in the last half century the huge island has lost about 70 per cent of its rainforest.

Palm oil, paper and coffee farming has continued its expansion, which has reduced the tiger’s habitat. When their habitat is encroached, this can lead the tigers to venture into human territory in search of food.

The result is what’s known as conflict tigers: the animal kills a human and in return the tiger is killed as retribution.

To try and reduce issues of conflict tigers the FKL rangers try to minimise the chance in the first place, by ensuring illegal encroachment of the habitat doesn’t happen.

The team, led by Dedi’s boss Rudi Putra, have been taking a chainsaw to illegal palm oil plantations since 2007.

The Leuser ecosystem is designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site and also is protected by Indonesia’s National Park system. The rangers identify the illegal plantations, confront the illegal loggers and then take a chainsaw to the trees. They have successfully restored thousands of hectares of habitat.

Ranger Jul.

Meanwhile, on our hike to the elephant bones, the light began to fade.

The decision was made to turn back. Nighttime is not a good time to be walking around the jungle with wild tigers.

Despite not seeing a tiger in the flesh, I felt their presence walking in their footprints through their realm.

That night back the ranger station we all huddled around Hendra’s computer. Hendra returned with a camera trap from the trail, which is a small camouflage box housing a motion-sensor camera.

Dedi popped the SD card into the computer and began to scroll through night vision video of the jungle.

Before long a male tiger filled the screen. But the majestic beast moved awkwardly, hopping, limping across a clearing. “Poachers,” Hendra said through clenched jaw.

Leaving the Leuser National Park by river canoe.

OUT OF THE JUNGLE

We left the jungle the following morning. After an hour-and-a-half journey down river in our motorised canoe, civilisation merged back into vision.

It started with the occasional canoe moored at the side of the river next to a hut. Then as we headed down river the number of huts and canoes multiplied, and before I could brace for submersion the sounds of engines, cars, horns and machines filled my ears.

The sight of a bridge with speeding cars and trucks came into view as we drew into dock at the village of Gelobmbang. The rickety wood jetty was a hive of activity as shirtless young men hauled palm oil fruit bunches off docked canoes. Another group of men operated a rust bucket machine, which made a heinous noise as it spat out shredded corn cobs into the water, creating a foaming cesspool of discarded corn, oil, trash, plastic bottles, a Coke can. A plastic bag floated by covered in something that looked like dried shit.

The smell of fuel and garbage mixed with the machine and the cars and lorries and I looked back up river to the jungle hills, where we had spent the last few days and where the tigers roam. And said the words, “What the fuck have we done?”

TIGER CONSERVATION

There are numerous NGOs and organisations working hard to preserve the Leuser National Park. For more information see below.

Love The Leuser

Orangutan Information Centre

Panthera

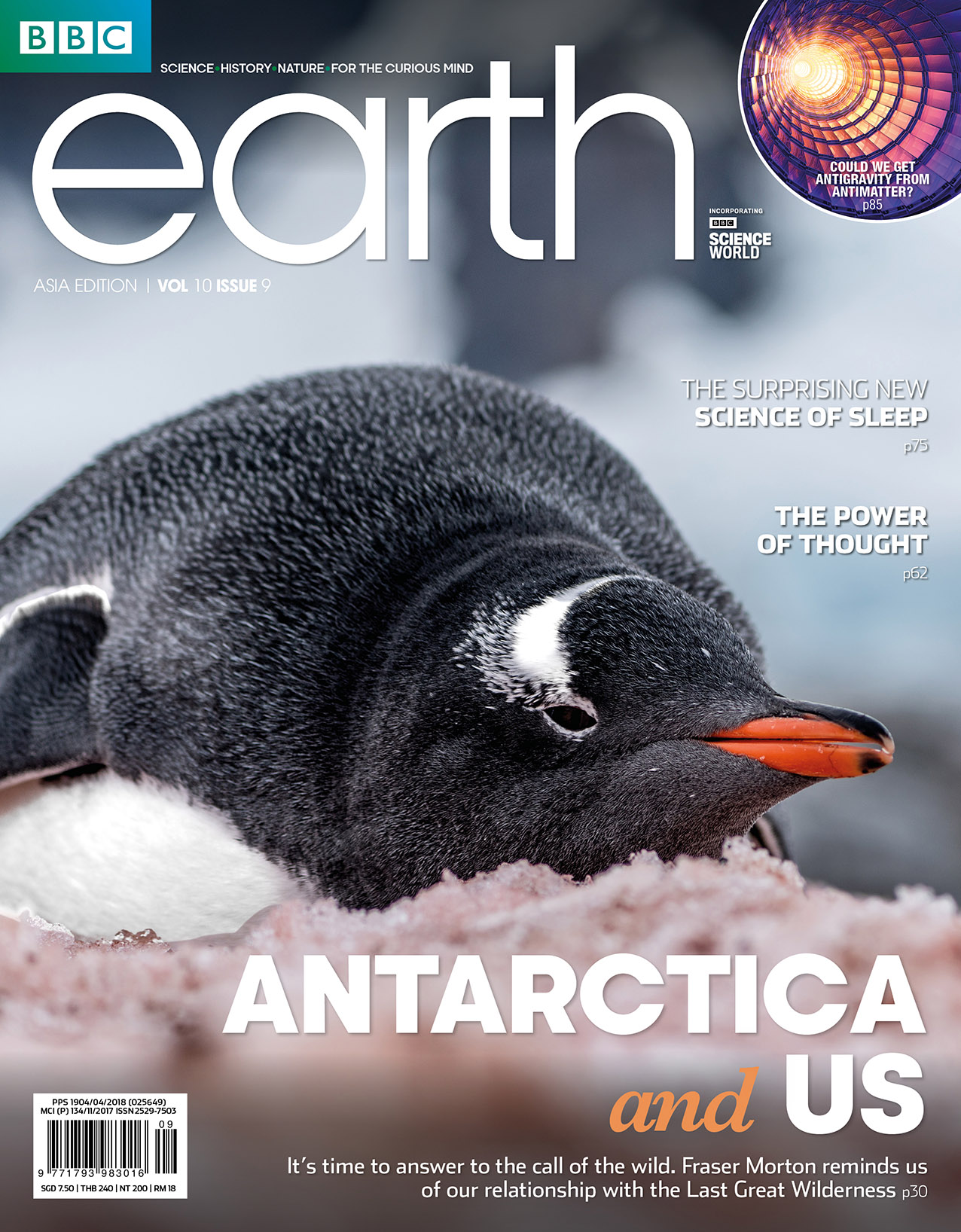

ANTARCTICA AND US

To stay wild the Last Great Wilderness needs us to keep it that way. Antarctica has reached into our hearts and minds and tugged at our adventurous spirit ever since the Ancient Greeks hypothesised that a great southern continent Antarktos had to exist.

TO STAY WILD, ANTARCTICA NEEDS US TO KEEP IT THAT WAY. PERSPECTIVES FROM AN ODYSSEY TO THE LAST GREAT WILDERNESS WITH A POLAR LEGEND.

FEATURE Nº19

BY FRASER MORTON

Antarctica has reached into our hearts and minds and tugged at our adventurous spirit ever since the Ancient Greeks hypothesised that a great southern continent Antarktos had to exist.

The continent has witnessed the best and worst of mankind’s relationship with nature – from darker days when the first sealers and whalers arrived in the 19th century and drove many species close to extinction, to a new dawn with the heroic polar exploration age from the 1890s to 1920s.

Since 1959, Antarctica has won our protection in the form of the Antarctic Treaty, a nation-binding agreement between 53 countries that keeps the pristine continent free from exploitation in all forms. It is the only free place left on Earth, owned by no one – a designated land for science and peace. The Treaty is regarded as one of mankind's greatest achievements.

However, the continent once again faces an uncertain future as a consequence of human meddling. The Treaty is up for review in the year 2041, and there are countries and companies already jostling for claims on the continent’s resources.

Meanwhile, climate change is warming the continent faster than ever, which means that we will begin to feel Antarctica’s power even more in the decades to come as ice-melt morphs into sea level rise, burying low-lying shorelines around the Earth.

It’s a time when our species and the seventh continent’s fates are intertwined and when our protective instincts need to guide our imaginations and actions once again.

ADVENTURE ACTIVISM

Earlier this year, I travelled to Antarctica for Eco-Business news and Channel News Asia to document a voyage with a climate change activism foundation called 2041, led by British polar explorer Sir Robert Swan and his son Barney.

In 1989, Rob became the first person to walk to both the South and North Poles. Since then, his mission has been to draw attention to the plight of the polar regions through activism, expeditions and renewable energy initiatives.

Our two-week voyage was joined by 90 people ranging from activists, scientists and teachers, to entrepreneurs and renewable energy specialists from around the world. My place in the group was as a documentarian, to film and photograph along with Singaporean environmental journalist Jessica Cheam a documentary about the expedition and climate change.

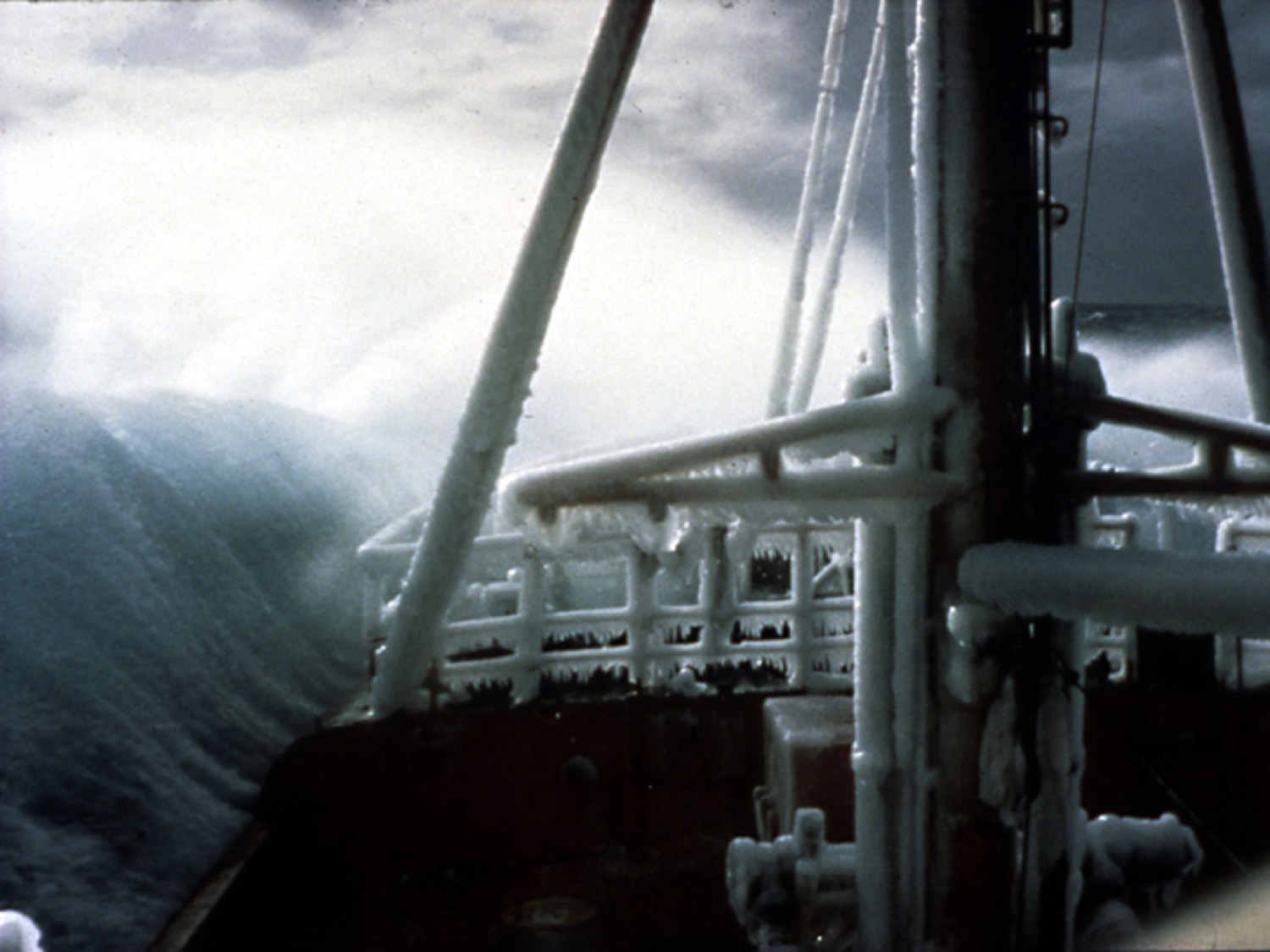

As the journey commenced, we sailed across Earth’s most treacherous sea crossing,The Drake Passage, all the while hearing stories of the Swans’ expeditions.

In January this year, the pair led the first-ever renewable energy expedition to reach the South Pole. They dragged sleds fitted with NASA-designed solar panels, used biofuels for cooking and survived solely on renewable energy. The expedition was 100 per cent carbon neutral.

While 61-year-old Rob had to turn back halfway, 23-year-old Barney made the full distance. The decision was one Rob said was the “hardest of his life”, particularly to leave his son to “face the terror of what was to come”.

Barney nearly lost toes, but the 56-day historic walk has now etched both their names in polar history.

“If we can survive in the harshest place on the planet, then why can’t we get our act together back in the real world, in order to use more renewable energy?” asks Rob.

His vision for climate change is simple: “It can’t be negative. Because people switch off. And no one I’ve ever met on Earth is inspired by someone who is negative”.

The Swans aim to inspire professionals and companies to live more sustainably and speed up our transition to renewable, clean energies.

“People thousands of years from today will be so proud of us if we just leave one untouched place on Earth for the sake of science and peace,” Rob says.

CALL OF THE WILD

Our voyage takes us on a zigzag route through the waters off the Antarctic Peninsula, one of the most stunning albeit fastest-warming places on Earth.

We see marauding monolithic icebergs slip past the ship. In the distance pristine peaks bestride the shoulders of glaciers that rise from the sea. We see breaching humpback whales, inquisitive leopard seals, legions of unafraid penguins and scores of albatrosses arching across the unblemished skies.

We encountered steep glaciers – more than 300 meet the sea on the Antarctic Peninsula – which flow downward and create iceberg factories on both the west and east coasts.

It is a place where the human body is feeble and “makes a mock of our puny existence” as polar legend Ernest Shackleton wrote during his doomed Endurance expedition. But the importance of a journey to Antarctica is what Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen would say is the “call of the wild”.

“The first great thing is to find yourself, and for that you need solitude and contemplation – at least occasionally. I can tell you this, deliverance will not come from the rushing noisy centres of civilisation. It will come from the lonely places,” he wrote.

To stay wild, Antarctica needs us. This is a fact often misunderstood. We banned whaling, put national interests and claims to one side and have put science and peace first, which must be commended. Just like Earth's great National Parks – Yosemite, The Great Barrier Reef, The Serengeti to name a few – which needed to be established and routinely patrolled to keep them safe from our own exploitative tendencies, Antarctica, too, needs our protection.

To remain a land of science and peace, the continent needs us to commit to the preservation of the Antarctic Treaty when it comes up for review in the year 2041.

In 1961, the signing of the first Treaty was a historic moment of international unity, which put the preservation of wildlife ahead of national interests. Since then, wildlife has flourished and scientific research has been shared, leading to a deeper understanding of how the continent affects the rest of our planet.

Through their 2041 foundation, Rob and Barney see the key to unlocking attitudes to the climate change issue in inspiring wonder and connecting people with the natural bounty of the continent.

They have taken close to 4,000 people on expeditions over the years to spread their renewable energy message. Each person who leaves their expeditions, including all 90 people on our voyage, leave with a set of solutions to take back and implement in their home countries – some big, some small.

“Young people today have a massive amount of information, what they don’t have is enough inspiration,” Rob says on the last day of our voyage. “And what we seek to provide in our small way is that inspiration.”

A map of Rob & Barney Swan’s 600-mile renewable energy march to the South Pole.

Their message has inspired thousands of 2041 participants and their communities over the years and led to hundreds of campaigns, along with renewable energy, solar lighting, clean up and education projects around the world. The goal is to create climate change champions who go back home after the expedition and spread their message to larger communities. Each individual on our voyage has gone home to implement climate action projects within their respective home countries. We had Tanzania’s first-ever man in Antarctica in the form of Erasto Njavike

McKunyopa. He is leading a reforestation program this year on Mount Kilimanjaro. Singaporean Inch Chua created an Antarctica soundscape theatre production, Team Zayed from the United Arab Emirates are championing solar light usage and marine conservation, Indian engineer Vijay Varada has designed an open source design for a wind turbine, which can be downloaded and 3D printed for free worldwide. Journalist Jessica Cheam and I hosted Antarctica photography and art exhibitions in Singapore. What's more, all of the remaining participants have pledged to engage and enlighten their communities with climate change projects.

Antarctica reached inside of all us and tugged at our protective instincts. As I realised at the end of the trip, the reason to visit the Last Great Wilderness is to bring back stories of its wonders and share the experience with others. That’s Antarctica’s greatest reward.

Any time I close my eyes, I can still see those unblemished peaks rising from the sea at the bottom of the Earth – where nature is wild and free.

As Rob rightly put it, “From now on, whenever you will look at a map, your eyes will go south to Antarctica”.

2041 International Antarctic Expedition. Photo by Trent T Branson.

2041

2041 foundation has a two-pronged mission: To protect the Antarctic Treaty, as well as to create climate change champions and promote renewable energy use through expeditions. Rob and Barney are on a seven-year Climate Force Challenge to clean up 360 million tonnes of C02 by 2025.

REACH OUT

If you would like to learn more about the Antarctic Treaty, or educate yourself on incorporating positive lifestyle changes and actions you can take to combat climate change, visit www.2041. com/education. If you are interested in applying for an expedition with 2041, contact info@2041.com or jeff@explorerspassage.com for further details.

This photo essay and article was originally published in BBC Earth Magazine, September 2018. Additional archive photography with thanks to 2041.com and group photo Trent T Branson.

MORE ANTARCTICA STORIES

MORE FEATURES

VAPE CARVERS

In Bali we find a confluence of culture where technology, art and vape intersect as a new subculture emerges. In a grungy workshop in Tampaksiring, Bali a master carver sits bare chested and cross-legged under the deathly stare of animal skulls...

FEATURE Nº18

IN BALI WE FIND A CONFLUENCE OF CULTURE WHERE TECHNOLOGY ART AND VAPE INTERSECT AS A NEW SUBCULTURE EMERGES

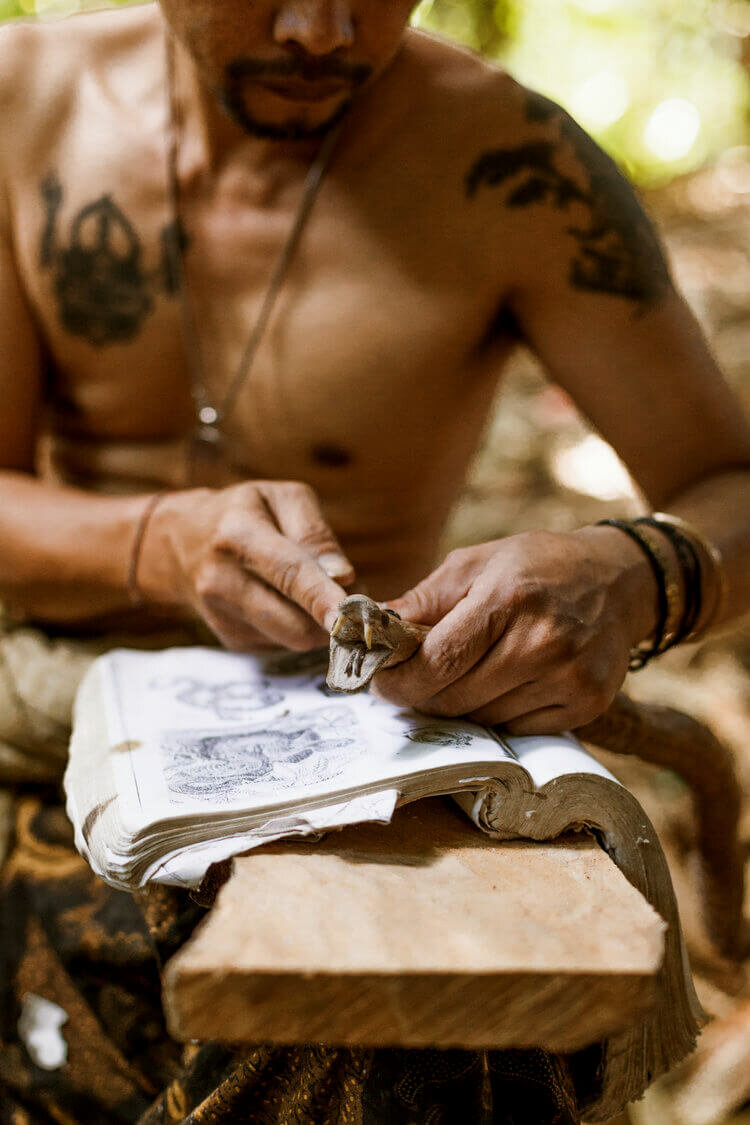

In a grungy workshop in Tampaksiring, Bali a master carver sits bare chested and cross-legged under the deathly stare of animal skulls.

His focus is fixed on what he holds in his hands. In his left, he wields a razor-sharp power tool. In his right, something new to these parts, a piece of wood composite onto which he carves a snarling Hindu mythological monster, known as a Raksasa, complete with the body of a snake and the head of a lioness.

He has carved the depiction many times. As a boy onto coconut husks, known as bomo, as a teenager etched into giant faces of ogoh ogoh statues used in the annual Balinese Nyepi celebrations, and later as a man onto the skulls of cattle where along with his friends he would form a renowned group of bone carvers from Tampaksiring sought after island-wide for their artisanal creations.

Today, however, he holds in his hand a creation new to Balinese shores.

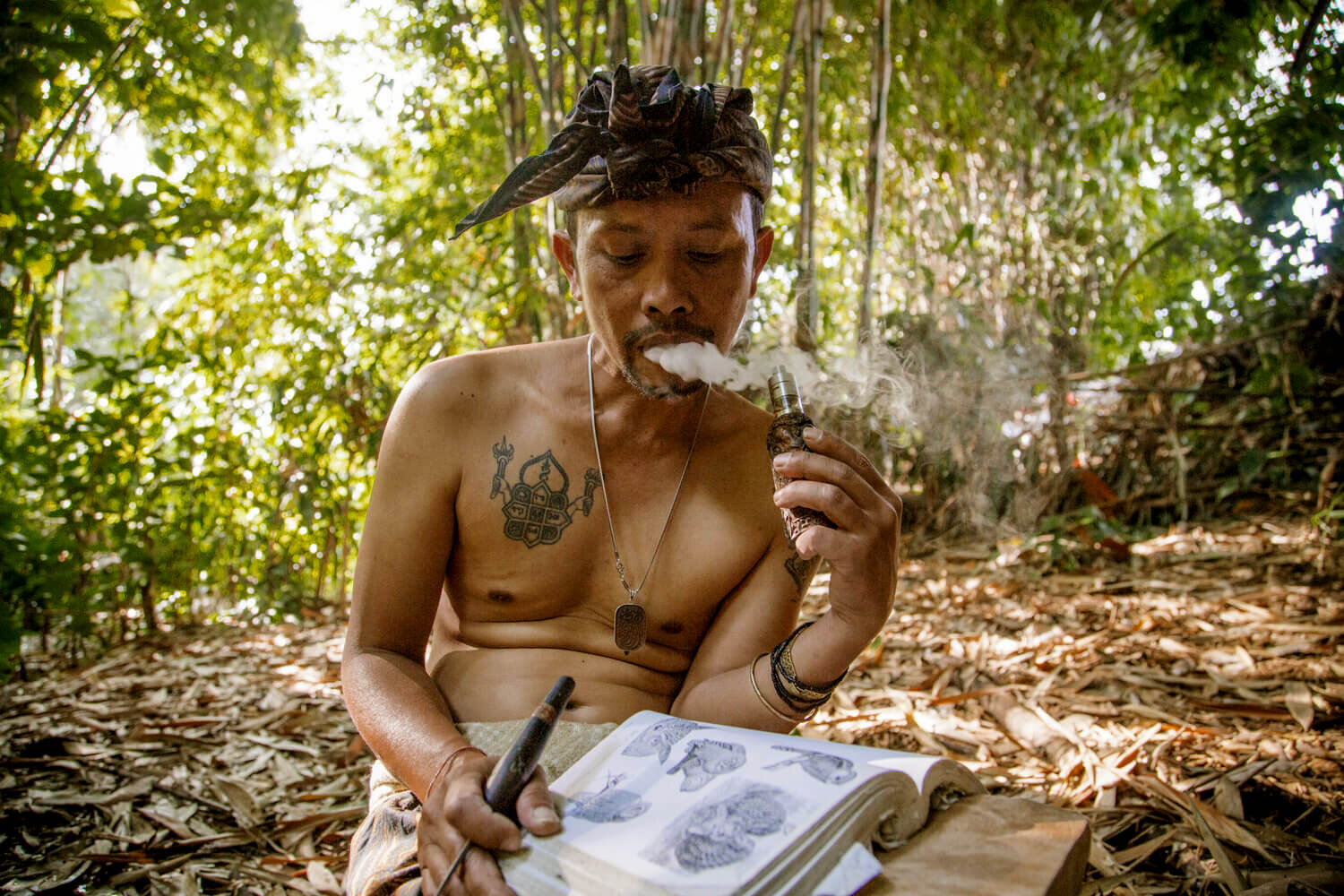

He raises the object to his lips, takes a deep inhale and blows an enormous milky smoke cloud into the air, which fills the dark room with sweet-smelling vanilla.

The vape device, or mod, he holds in his hand is an US$800 intricate work of Balinese art, which he has spent the past two weeks toiling over.

His name is Wayan Tegal and he is one of the “Raksasa Carvers”, a group of artisans who have found a new niche amid a vape fascination currently gripping Indonesia’s youth culture.

Carver Wayan Tegal in the early hours near his home in Tampaksiring, Bali.

Times Of Change

Bali is changing fast as foreign and domestic forces collide all around the island. The edges of tradition, tourism and technology trickle into each other in a soup that’s not yet found it’s flavour. In the tourism beach areas thousand-year-old temples sit sandwiched between surf stores and burger joints, while new modern hotels rise above it all. It’s a time of rapid change and contrasts.

Bali’s famed carvers have also felt the touch of modernisation and in recent years the Tampaksiring carvers have fallen on hard times.

A number of factors have contributed: The domestic market demand for their intricate artisanal carvings has waned in the face of faster, modern carving techniques with an emergence of production-line carving methods, putting speed ahead of substance.

A Raksasa vape mod.

Intricate bone carving.

Intricately carved animal skulls at Wayan Tegal's workshop.

Today, the smartphone as a travel companion is also having real world effects on the Balinese carvers’ livelihoods, with many artists reporting a worrying trend: Tourists are reaching for their phones to take photos of their art rather than their wallets to pay for pieces.

“Our competition is with technology,” Wayan Tegal says. “With technology today, one speed, or one click on your phone is all that it takes. You can do anything with these devices, but when we use our feelings as tools when we make art, the result will always be better.”

Meanwhile, in the previously lucrative tourism sector the carvers have seen demand dissipate for more expensive, larger and intricate wood carving pieces and replaced by a trend where people want cheaper, smaller pieces in quantity vs quality. This has forced the carvers into a creative conundrum: quantity and money vs quality and artistic fulfillment.

“When technology make things, they are going to look exactly the same, but it's different when we make art. Art is more...it has life, it has soul,” Wayan Tegal says.

Much like Bali today, the carvers stand straddling the intersection of technology, tourism and their ancient traditions.

Therefore, in a bid to earn money, the carvers have moved in recent years to make products that abandon their artisanal carving methods, such as wood plug earrings, trinkets and smaller easy to produce knick-knacks.

Master carver Lumbung.

Wayan Tegal holds one of his kris knife creations.

Art And Soul

Tegal and the other Raksasa Carvers - six in total - believe when they create a piece of art out of creative compulsion opposed to money they imprint what they call “taksu”, or magic onto the piece.

“When we showcase our creations that are distinctively Balinese, and we do it with feelings, all these ideas that we have come to life in our art,” Tegal says.

Sit with the carvers long enough and they will regale you with tales of monsters and Hindu mythologies they envisage during meditative states before they begin carving on their quests to achieve taksu. As with all traditional carvers, they pray to the wood they use, observe rituals passed down to them and see their art, faith and soul intertwined.

A Balinese teenager blows vape rings at an ogoh ogoh burning.

Wayan Tegal watches one of his ogoh ogoh statues burn to ash as is tradition following the annual Nyepi celebrations.

Vape Culture

Additional reporting by Risyiana Muthia

Indonesia has one of the world’s highest smoking rates among men with 65 per cent of the population hooked.

Tobacco companies in Indonesia have major sway over the culture influence. Advertising is allowed and actively promoted specifically to the country’s male youth. Stop at any traffic light intersection and you will see a billboard with a Eurasian male model staring back at you with a babe or bike in the background and a pack of cigarettes superimposed with a stamp of approval over the entire scene.

Teenage boys in Bali and Indonesia grow up surrounded by cigarettes at home, in advertising and engrained in their culture.

Smoking here is a male-dominated addiction as only five per cent of women smoke, according to latest statistics.

In recent years, smoking cessation has entered the public conversation in Indonesia led by the vaping phenomenon that has developed into a US$8 billion industry worldwide.

With such a large slab of Indonesia’s male population smoking it’s no wonder vaping has caught on in a huge way. Bali is no exception and around the island hundreds of vape cafes have been established.

Walk into one and you will most likely walk through sweet-smelling cloud and find the young owners sitting in a haze of smoke surrounded by hundreds of bottles of vape liquid - ranging from nicotine-infused, coffee, mango to even flavours such as pancake, fruit loops and bubblegum.

Vaping faces backlash as more researchers investigate the long-term health effects worldwide.

However, there are thousands of cases of people who have quit by using vape devices with and without nicotine-infused liquid inside.

There’s a general consensus at present that vaping is a harm reduction device to replace smoking, not as something advisable to start if you have never smoked.

Vaping has been proven to be healthier than smoking and that is making tobacco companies nervous as they rush to try and control, and in many cases stamp out, vaping.

Today, a slew of regulations worldwide are coming into effect while tobacco companies try to invent their own e-cigarette devices to win back millions in lost revenue.

In Indonesia a recent article by the Jakarta Post reports “a 57 per cent tax on non-tobacco alternatives starting this summer”.

And late in 2017 Indonesia’s Commerce Minister announced that all vape shops would need to comply with regulations from the Ministry Of Health and National Food & Drug Agency as well as hold certificates from the country’s National Standards Agency. It seems vaping could be about to get steamrolled with paperwork, but not without a fight.

Today in Bali vape culture is booming. New cafes continue to open all over the island. There is even an “Asosiasi Vaporiser Bali”, or Bali Vape Association (AVB), established in 2015 and with 100 small business owners, mod and liquid manufacturers who actively campaign to keep vaping free from scrutiny.

Founder of AVB Ida Bagus Manobhawa is positive about the future of vape in Indonesia.

“We organise a lot of social events and try to work together with the government to counter any misleading information about vape...Their response has been very positive towards the vape community and small businesses in Bali. So far, there hasn't been any ban when it comes to vape distribution and production. Vape is legal.”

Ida says AVB’S main concern is with the media and lack of balanced reporting on the subject of vape.

“We think the negative reporting around vape is biased, and many use old and questionable sources. They don't want to use new research that shows how vape is safe for use.”

As vape grows in popularity in Bali, competitions and meet ups are being staged, hundreds of Instagram accounts have been created and independent cafes and social media buzz with the chatter young Balinese men comparing vape mods, liquids and paraphernalia.

A new subculture, industry and micro-economy has been born, where the Raksasa vape carvers have found a means to make money and fuse their passion for their culture.

Cattle skulls prepared and stored for carving.

A Raksasa mod in the making.

Young apprentice carver in Tampaksiring watches Wayan Tegal work.

Where A New Subculture Is Born

Stare at one of the Raksasa vape mods long enough and the level of detail is hard to comprehend. The artistry comes at a hefty price tag of US$800, but are aimed at the high-end vape collectors and sold locally and internationally.

All of the Raksasa carvers say they have given up cigarettes since being introduced to vape and are hopeful they have found a line of products that can reignite consumer passion for their work by appealing to a new, younger audience.

“With the ideas we have now people are more excited with the vape mods. Before Raksasa Mods was born, the plain ones available in Bali were not not pieces of art and were not interesting.”

“We put our culture inside these vape mods. They are alive with taksu."

To understand the carvers’ passion you have to sit with them for a day observe.

Tegal sits for hours under a canopy of vanilla smoke on the floor surrounded by his workers with a look of serene concentration of his face. Smoke pours out through the cracks in the grimy cement walls and the sound of electric saws, drills and needles on wood fill the air. Occasionally his son and gaggle of friends run through the workshop and watching over the whole scene are rows of hanging skulls - bulls, cows and goats - that each have intricate Balinese patterns and mythological characters engraved into their skeletons.

They are relics of the bone carvers past and how they came to fame in these parts. Previously, these skulls were the canvas and commodity of the time.

Watching Tegal work a realisation comes to mind that for the carvers the nature of their canvas is not important - bone, wood, statues, paper or composite - but instead following their calling to the craft for the sake of creativity. Nothing more, nothing less.

For now, they are vape carvers.

“In Bali to survive with art we have to do it with feelings and with heart. We can do more than what machines can do and this is our competition and our battle now. Not everything can be valued with money or wealth. It’s how we can be valued through conserving arts and culture that we have in Bali that is important to us.”

MORE FEATURES

THE STREET SADHUS OF RISHIKESH

As dawn rolls over the shoulders of the Himalayas each morning hundreds of devout Hindu holy men bask in sunshine and bathe in azure waters of the Ganges River. The Sadhus of Rishikesh are a striking sight.

FEATURE Nº17

Photography by Eszter Papp

Words by Fraser Morton

As dawn rolls over the shoulders of the Himalayas each morning hundreds of devout Hindu holy men bask in sunshine and bathe in azure waters of the Ganges River. The Sadhus of Rishikesh are a striking sight.

A Sadhu holy man with his donation jar.

A sadhu who sings Bakhti flow at the same spot each day.

They emerge from street corners, shacks on the banks of the mighty Ganges River or from nearby Ashrams. Some smear on face paint of vermilion and sandalwood ash, some adorn saffron robes and intricate gold chains and rings, while others wear only a loincloth or nothing at all.

Unlike the putrid waters in Varanasi, The Ganges in Rishikesh is azure and clear.

These devout holy men live on the fringes of Indian society. The Sadhus have purged themselves of the 21-first century, all worldly possessions as well as their families, choosing instead to wander India on a spiritual quest of devotion.

They live on the generosity of strangers and are revered by many Hindus for their sacrifice to their faith.

Despite owning nothing other than walking sticks and donations pots, the Sadhus take pride in their appearance - a form of artistic expression in honour of the gods.

Many sects of Sadhus dress in colourful regalia.

Some Sadhus also accept donations of ornate jewellery.

While there are many - around 60 - Sadhu tribes around India, most notably in Varanasi, there is also a large population of these nomadic holy men drawn to Rishikesh, one of India’s most sacred sites, where sages and saints have embarked on pilgrimages to meditate and attain higher spiritual insight for centuries.

While the banks of the Ganges in Varanasi is considered the holiest of places for a soul to be liberated and enter the afterlife, Rishikesh is also a source of many holy rituals on the banks of the great river.

Street scenes from Rishikesh.

The Ganges River is living and divine in Hindu Indian society, in part due to its source being meltwater from Himalayan snowfall from the heavens above.

The Sadhus also act as spiritual mentors, telling fortunes, interpreting dreams and playing music for passersby.

Many Sadhu also puff on marijuana and hashish each day, which they imbibe in a variety of pipes or rolled joints.

Cow blessing.

A mass ceremony on the banks of the Ganges.

The road to becoming a Sadhu is as diverse as the sects of Sadhu themselves. While some are orphans, others have university degrees and were previously rich men who denounced their former lives. Some have no one and others have families who have no idea of their whereabouts. The Sadhu don’t want to be found.

Some undergo an initiation to become a Sadhu, with more extreme sect rituals include covering themselves in human ashes, devouring human flesh and worshiping the skulls of the deceased.

Not all Sadhus do this, however, and if you happen to travel to Rishikesh you will no doubt encounter these holy men living a life-less-ordinary: Singing, studying their faith and extending a hand and smile to strangers.

STREET GALLERY

MORE FEATURES

THE LOCH NESS HUNTER

Meet the Loch Ness Hunter. In 1991 Englishman Steve Feltham sold his house and all his possessions to embark on a quest to unravel the mystery of the Loch Ness Monster. He expected to be gone for two years. Twenty-six years later and he’s still searching.

FEATURE Nº16

WE MET THE MAN WHO HAS BEEN SEARCHING FOR SCOTLAND'S MYTHOLOGICAL MONSTER FOR 26 YEARS

Words by Fraser Morton

Photography by Eszter Papp

In 1991 Englishman Steve Feltham sold his house and all his possessions to embark on a quest to unravel the mystery of the Loch Ness Monster. He expected to be gone for two years. Twenty-six years later and he’s still searching.

“I’ve been here a long time, but this is my chance to solve one of the greatest mysteries ever,” Steve said, leaning on the door of his caravan at the North end of Loch Ness.

Steve, 54, holds the Guinness World Record for the longest continuous search for the Loch Ness Monster and has been named a tourism ambassador for the region. He’s a tourism draw in his own right.

The mystery of Loch Ness has drawn people from around world for the past 90 years – but Steve is the only person to dedicate his life to unravelling the truth.

He says his quest is not to prove the existence of a monster, but to find out the source of the alleged sightings.

Steve Feltham outside his caravan at the north end of Loch Ness.

The Legend

The first record of Nessie can be traced to Irish monk St Columba, who allegedly banished a beast to the River Ness in the sixth century.

It was 1933, following the opening of a new road that lined the loch, when the first sighting was reported by a couple who claimed to see an enormous dragon-like creature crossing the road with an animal in its mouth. The Inverness Courier published the story, which received widespread international media attention and the coining of the name the “Loch Ness Monster”. Two more sightings were reported shortly after. Hugh Gray while walking his dog took a blurry photo of what he claimed was the monster, followed by motorcyclist Arthur Grant, who reported that he almost hit a creature resembling an enormous seal with a small head and long neck on a moonlit night. He said the creature darted across the road and slipped into the loch.

Shortly after, the Daily Mail newspaper sent renowned tracker Marmaduke Wetherell to Loch Ness. He reported back what he found: Large footprints in the mud on the shores of the loch.

However, it turned out there was a popular trend among affluent travelers of the day. To make picnic tables made from elephant feet. The tracks turned out to be the prints of the grisly picnic tables.

Humiliated, he hatched a plan to regain his reputation. He would make a fake monster. He enlisted the help of his son-in-law Christian Spurling, a model maker, Maurice Chambers, an insurance agent and his son Ian Wetherell, who would buy the materials needed for the hoax. A small toy submarine onto which they affixed a neck and head of a monster and then motored it out onto the loch. Ian Wetherell then snapped a few frames, but as they heard the water bailiff approach they sank the toy submarine, where allegedly it remains to this day at the bottom of the loch.

Chambers then gave the photo plates to Robert Kenneth Wilson, a friend and gynecologist from London who loved a good practical joke. He developed them in Inverness and sold the photos to the Daily Mail who ran the headline on the front page: Surgeon’s Photo Of The Monster. Some 60 years later the photo was proved to be a hoax.

Despite the scandal, alleged sightings continued from the 1930s to present day.

There have been numerous efforts to find Nessie, with absurd and professional expeditions onto the loch by boat and via airplane.

The most notable was in 2003 when the BBC funded an extensive scientific mapping of the loch with 600 sonar beams. The study concluded there was “probably nothing there”.

Steve's Story

It was 1970 when Steve was seven years old and a family trip to Loch Ness that planted the seed for his obsession.

At the time there was a Loch Ness Investigation Bureau, and Steve said he was captivated by the “grown men with huge cameras searching for a monster”.

His father bought him a book on the history of sightings and from then on young Steve was hooked. All through his adolescence and into adulthood he came back on week-long expeditions armed with basic cameras.

He worked as a potter, a bookbinder and then a graphic artist, but the loch kept calling him back.

So on June 19, 1991 after ending a relationship, selling his house and loading his possessions into a former mobile library van, Steve headed for Scotland and to the shores of Loch Ness.

Soon after, the BBC caught wind of his ambitious plan and thought it worthy of a story. They kitted out Steve with all the camera equipment and tape he would need to document the loch for an entire year.

The program Desperately Seeking Nessie aired in 1992 and was a hit. Tourists began arriving in droves to knock on Steve’s van door. Word was out, there was a real Nessie Hunter on the case.

It was in this first year when he made his only sighting.

“It was like a torpedo moving through the water, like a white streak of water. Almost like a water skier,” he said. “To this day I can’t explain what that was.”

Steve says the most compelling sighting happened in 2012.

That was when local tourist boat skipper Marcus Atkinson recorded a sonar image of an alleged five-meter wide object at a depth of 75 feet directly underneath his vessel.

“He had just dropped off tourists at Urquhart Castle at the edge of the loch and was idling in the bay when he saw the object on his sonar.”

The sonar image was sent to the press and made national headlines. It showed a grainy large mass of something at about 75 deep and five feet wide under the skipper’s boat.

At 23-miles long the loch was too big for one man to cover, and Steve could only search about a mile of water from each vantage point he visited.

He tried other methods of hunting. He used a boat fitted with echo sounders and even took to the skies in his friend’s micro-lite.

For most of the first decade, Steve’s van was mobile and he changed vantage points, but after his van failed an MOT, he decided to hold up in the peaceful village of Dores at the north end of the loch.

The owner of the Dores Inn – the local pub -allowed Steve to build a small wood decking on the beach and even hook up his van to their electricity. He made himself at home. To earn money he started making little Nessie models from clay to sell to tourists.

Despite his remote lifestyle, Steve says he’s never lonely. He’s met people from all around the world. A Chinese travelling circus arrived one day, and on another occasion comedian Billy Connolly knocked on his door to ask Steve to be his personal guide for him and his pals.

In 2015, Steve was interviewed by a freelance journalist and mentioned that one possible source of the sightings could be a very old Wels Catfish, which could grow to 13 feet and 62 stone.

He said, “It is known they were introduced into lakes in the UK in the Victorian period for sport fishing".

The story went viral and within a day Steve’s catfish theory had made its way around the world.

“There are many different theories. Some people believe the catfish story. Others think there’s a spaceship on the bottom of the loch and the popular one is that Nessie is a lost dinosaur. None have been proved, and that’s what I’m trying to get to the bottom of.”

Steve makes money selling clay Nessie models.

It’s not just the mystery that keeps Steve on the banks of Loch Ness.

“There’s a palpable energy around this loch. At night is when I like it best. I go out and stand on the beach looking out over the water. It’s a magical place, especially when the stars are all out."

Steve has claimed the mantle as the official Nessie Hunter of the area. So on the rare occasions when sightings do happen, they go to Steve. He helps publish the photos, and in most cases is able to identify the objects: tyres, small boats, tides and other normal explanations.

Today, Steve says the type of traveller coming to the loch has changed.

“People come these days and take a photo of themselves and then leave pretty quick. They seem more concerned with themselves than appreciating the beauty here.”

“There used to be a lot of independent travellers who come and camp. We get a lot of bus tours now...changed days.”

Ask Steve why he’s stayed so long and he smiles.

“Well, it’s an adventure isn’t it. It’s out of the ordinary. If that little seven year old boy could see me now, he wouldn’t believe his luck.”

I WAS SHOT IN JOBURG

That day we met the "I Was Shot In Joburg" boys. A collective of former street kids turned artists using disposable cameras to document their surroundings in Johannesburg, South Africa.

FEATURE Nº14

THE FORMER STREET KIDS WRITING A NEW FUTURE THROUGH

PHOTOGRAPHY AND THE ART OF BUSINESS

By Fraser Morton

In a dilapidated ghetto of Johannesburg a former street kid stares at a crumbling wall graffitied with the words, “Write The Future”. There’s a click of a disposable camera shutter and the kid has his shot. The image will go on to sell thousands of copies - printed onto notebooks, canvasses, keychains and postcards - and ferried to all corners of the globe by tourists. The boy will go onto become a photographer and a businessman.

He is one of many success stories from the "I Was Shot In Joburg" arts collective.

The "Write The Future" notebooks have been a huge success for the collective.

Two of the "I Was Shot" photographers at a cafe on Arts On Main.

Author's stash.

Nelson Mandela as a young boxer painted in a giant mural in downtown Johannesburg. The "I Was Shot" collective sell prints of this image.

“I Was Shot In Joburg” was established as a community project in 2009 by South African photographer Bernard Viljoen to provide a platform for disadvantaged street kids to learn photography and business skills to empower them to turn their lives around.

“What I would like to propose for the project is using my photographic skills and talent and give of my time and resources to make a positive contribution to and enrich the lives of kids who might otherwise not have had the exposure nor the opportunity to develop their own photographic skills and talent,” Viljoen said.

The “Write The Future” print is just one successful product the young photographers sell at their Arts On Main studio, a mixed-use creative hub in Johannesburg’s arts-gentrified neighbourhood in the Maboneng Precinct.

The boys making photo frames from old magazines at the "I Was Shot" studio.

A local street seller hawks his wares on Arts On Main.

The young students learn photography, craft skills to make prints and other products to sell their work and business acumen. They also learn how to open a bank account and manage money for themselves for the first time.

“Teaching and enabling them to see the world through different eyes. Teaching them to look, to see, to compose, to capture what it is they see in a such a way that they can be proud of it,” Viljoen said.

The gentrified area today is clad in street art the boys photograph.

The boys on one of their daily photography tours.

---

I met the collective in 2016 while shooting a short commercial film about their work along with producer Ahmad Yusman and journalist Nastasya Tay for Click2View and VISA. We spent the day with the boys and Bernard walking the neighbourhood of Arts On Main. The photos on this page are from that walk as we filmed them capturing their photos. A great group of guys, collective and cause using creativity for the good of others.

Visit "I Was Shot In Joburg" here

FEATURES

SECRETS OF THE SIKEREI

There's no distinction between daily life and the divine on Siberut, the largest island in the Mentawais and where we have travelled 60 kilometres upriver to meet animist jungle-dwelling shamans.

FEATURE Nº13

A JOURNEY TO MEET THE SIKEREI SHAMANS, WHOSE SECRET LIVES IN THE JUNGLE ARE UNDER THREAT BY MODERNISATION.

There's no distinction between daily life and the divine on Siberut Island, the largest island in the Mentawais and where we have travelled 60 kilometres upriver to meet animist jungle-dwelling shamans.

The half-naked tribesman hacks down a sago palm tree, fishes out a massive worm, squeezes it dead and stuffs it into his mouth. His name is Kapik Sibajak, and he is a Sikerei medicine man of the indigenous Mentawai Tribe, and our host for the next few days.

Kapik Sikalabai and her sister about to begin a day's fishing.

The night view from Kapik's longhouse, known as an uma.

The Sikerei are a special class of male forest shamans and healers. They practice animism, wear hibiscus flowers, ink themselves with magic tattoos and sharpen their teeth. They have resisted evangelism, modernisation and government attempts to get them to both resettle and abandon their non-sanctioned beliefs. They have endured and, thanks in part to a trickle of tourism, now are largely left alone to live how they please in the jungle.

Earlier that day we had traveled for two hours upriver with our guide and translator Yen, a relative of the tribespeople, from his home village Muara to our rendezvous with Kapik. He appeared from nowhere from behind a tree in dense jungle wearing only a loincloth, bow and arrow, machete clasped in hand. Kapik loves that machete. It never leaves his side. He’s 69 years old and a prankster. He danced around us as we arduously trudged through knee-deep mud, waded through rivers, tightrope-walked log bridges, and picked and fought our way through the jungle in a race against darkness. He would disappear only to emerge a moment later, bursting into song, shaking his hips and motioning seductively to Eszter. I liked him immediately.

Hunting for sago worms.

Sago worm.

Making clothes.

Kapik is incredibly hard working, despite his age. Daily chores include tending his pigs and chickens that live under his longhouse, known as an uma, hacking down sago trees, fishing, and foraging. He smokes constantly. They have few pleasures here in the jungle and are heavily addicted to nicotine and sugar—gifts that you must come bearing in order to be granted shelter. Our host family— Kapik and his wife, Kapik Sikalabai, along with their middle-aged son Petrus Sekaliou, his wife and their two children, who came from their own home to meet us—is mischievous, loud, flirtatious and hard, but also affectionately hospitable. Kapik is a keen kisser. Both Eszter and I received frequent kisses on the cheek from him.

Kapik Sibajak, Sikerei medicine man.

Over a dinner of plain rice and noodles, Yen intermediates our chat about life. I’m keen to learn everything I can, but also for them to know a little about us, too. Kapik’s four sons are all married and living nearby—but on the outskirts of the forest, where they eschew tattoos and now wear western clothes. I tell them I’m from Scotland and that we too have tribes, called clans, and tribalwear. He’s amused. I show them a photo of a Highlands cow I keep on my phone, and I think Kapik Sikalabai looks impressed. I ask Yen, “Have they ever seen a horse?” When they say no, I pull up a photo of horses I took in the caldera of Bromo Volcano. “Java horses,” I say.

Kapik Sikalabai asks Yen where it is, he tells her Indonesia, and she looks surprised.

Making bamboo mats.

Kapik tending to his pigs.

Making clothes from trees.

Later that night, Eszter and I duck outside the hut for some air and are sucked into a night sky alive with stars, which swallows the jungle, our small hut and both of us in a mesmerizing star-spangled indigo blanket. On the stoop of that shack far from home, amid the snorts and smells of pigs, we stare skyward in wonder until we both laugh out loud.

Poison darts.

I shouldn’t be surprised when that dreamlike serenity is shattered at 3:37 a.m. We are asleep on the wood floor of Kapik’s uma when the screaming starts. It’s the pigs. In the pale moonlight that slices through the open-air hut I see the naked figure of Kapik carrying his machete and striding into the darkness. A second later there’s a sickening clang of metal, a dull thud and what sounds like splintering bone. I really hope it’s not the pigs.

Kapik's sister fishing for river shrimp.

Kapik Sikalabai

River shrimp.

I slip under the mosquito net, flick on my torch and head towards the light coming from the back of the hut. I hear laughter and another clang of a machete followed by a thud, more splinters and a nasty squelching sound. I see them now huddled around a flame torch, all six of the family. Kapik swings his machete and brings it down fiercely onto a log, which splits in two. He pries the glistening pieces apart with the tip of his machete. The logs are writhing and moving on the surface: worms. Hundreds of them. Long, thin, squirming worms ooze from the logs and everyone snatches them up and stuffs them into their mouths. Fat, tree-eating worms, they think, make for a sweet-tasting midnight snack. Kapik spots me, turns machete in- hand, laughs and shoves a worm in my direction. I hate it when this happens on travel assignments. It means I have to eat it. I can still feel the wriggling in my belly as I write this.

MORE FEATuRES

LONGNECKS OF LOIKAW

In the mountainside villages on the outskirts of Loikaw, Myanmar live the longneck ladies of a tribe carrying on a curious tradition steeped in mystery that is now entering an uncertain future, where tourism meets tradition.

FEATURE Nº12

A NEW TOURISM CHAPTER FOR THE LADIES OF LOIKAW

By Fraser Morton

Photography by Eszter Papp

It's a mystery why the women in Loikaw began wearing gold rings around their necks, even among the tribe themselves.

One story claims the rings stopped tigers from dragging women away by the neck. Another tale goes that it was to lure men from other tribes, and yet another suggests it was simply a fashion fad that caught on.

Whatever the origin, the longneck ladies of Loikaw are renowned throughout the troubled Kayah state of Myanmar, and they are the reason for a spike in travellers heading here in recent years.

Handmade Loikaw cotton scarves.

Cotton farming was the main income for the ladies before tourism.

From the 1950s until 2013 the state was a war zone between the military and armed ethnic groups that displaced thousands of refugees to Thailand and was locked off to the outside world.

However, since the country's first democratic elections in 25 years took place in 2015, this long-time off-limits - and one of the poorest regions of the country - is building a future chapter of prosperity, with new guesthouses, restaurants, infrastructure and jobs being created to meet the tourism demand.

The new face of tourism comes with challenges for the longnecks ladies, too. There’s already fierce debate among the traveller community about the villages being turned into “human zoos”. A claim based on the assumption that the tribal traditions are being transmuted to cater to the tourism intrigue.

There has been efforts to build a sustainable tourism model, and in 2014 an initiative was launched by the United Nations World Tourism Organisation to create jobs for the local communities and rebuild ethnic villages following decades of obscurity. An award-winning film was also made to promote the region, which you can watch here

Mu Aye on the stoop of her home.

In the kitchen of her home she shares with 6 relatives.

We spent an afternoon in Pan Pet visiting the longneck ladies - who also don’t mind being called this contrary to popular belief - and what we found was far from a human zoo. We found people proud to share their customs with strangers.

It’s a still place. There’s hardly any sound. A light whistle of the wind and the occasional groan from a meandering cow, but other than that there’s silence.

Located along a bumpy dirt track about an hour’s drive into the hills from the state capital Loikaw, today Pan Pet is undefiled by tourism. There’s a market on the edge of the village where we saw a road-beaten traveller buying a scarf from a longneck lady. Entering the village is unremarkable and consists of a collection of about 20 stilted huts surrounded on both sides by sparse, parched cotton-fields. Everywhere there is red dust. The heat is searing. Homes have no doors or windows, a simple wood fire in a large room and two small rooms with a mat on the floor to sleep. The stoop is the communal area and where the ladies sew and hammer their rings.

The longneck ladies live in their huts with their families and extended relatives and spent most of their days sewing scarves and garments that they wear and also sell to visiting travellers.

Rice wine.

She sometimes drinks a pot a day.

We sat on the stoop of Mu Aye’s home for a few hours, chatting and sharing a pot of pungent rice wine. Her neck and legs were bound with rings and she wore full traditional wear of her tribe.

She told us she has been wearing the rings since she was six years old. She didn’t know the origins of the tradition, and she told us the tiger story, the fashion story and the love story. She said they all could be true.

She told us that before 2013 her and the other women relied solely on making money from cotton farming, about US$20 per month. Today, each tourist - of which she gets about 10 per month - pay US$2 to visit her homestay and she makes extra money selling her handmade scarves. We bought three for US$15. She says she would much rather be making her garments than farming.

“We plant cotton in the fields. We harvest cotton in the cold season, and my hands hurt with the freezing cold,” she said.

“There’s also no water when we are working in the fields. I prefer to stay with my children and make garments.”

Mu Aye previously worked at a handicraft tourist shop at Inle Lake, where she sat for hours in her traditional dress to gain the attention of passing tourists to pose for photos in exchange for money. A job she didn’t like because she missed her family. So the issue of exploiting these women tradition purely for tourism is present, but she says this is not the case in Pan Pet.

Mu Aye says she is unsure if children will continue to wear the rings.

"Not many girls wear them now. Some do, but not as many today as when I was young, but I do hope our tradition will live on."

Before we leave we ask Mu Aye if she has any hopes for the future?

"I’ve always wanted to see Yangon," she said.

MORE FEATURES

CHOLITA WRESTLERS

The indigenous Bolivian women fighting stereotypes and grappling with decades of discrimination through wrestling. A night spent ringside with the Cholita Wrestlers.

FEATURE Nº11

The indigenous Bolivian women fighting stereotypes and grappling with decades of discrimination through wrestling

Words & photography by Rob Bain

At 4,150 metres above sea level in the Andes cloudline lies one of the world’s highest wrestling rings. It's Sunday afternoon in El Alto, Bolivia and that means one thing: Fight night is upon us.

Each week locals and tourists cram into the Multifuncional Ceja de El Alto Stadium to watch the sports spectacle, known as Cholita Wrestling.

In the past “Cholita” was used as a derogatory term, meaning a lower-class woman of mixed indigenous heritage and identified by their bowler hats, puffy skirts and shawls. Today in El Alto, the Cholita female fighters still don the same dress but are now the heroines the crowds come to see.

Backstage before the mixed-gender bouts.

Wrestling has been popular in Bolivia since the 1950s among men, but it wasn’t until 2000 when the Cholitas entered the spotlight. At first it was a way for a few female sufferers of domestic abuse to learn fighting skills, but it wasn’t long before a boxing promoter Juan Mamani made the Cholita fighters a household name.

Cholita outifts consist of the trademark bowler hats, puffy skirts, shawls and jewellry.

Male wrestlers wear elaborate good-and-bad-guy outfits.

Since 2011, the Cholitas have formed their own independent wrestling association, which is similar in style to Lucha Libre, or Mexican Wrestling, however, the events here in El Alto focus more on audience entertainment and storylines between the wrestlers rather than the physical rough-and-tumble.

He thinks he means business.

The undercard usually involves a couple of bouts between male wrestlers to get the crowd warmed up before the main event. Hushed anticipation follows as the Cholitas enter the ring wearing their iconic long skirts, jewellery and colourful cardigans. Despite the obvious staged moves, once the bell rings all hell breaks loose with body slams, clotheslines, tombstones, submissions, gags, occasional blood and plenty of laughter.

One after the other their larger male opponents are counted out while the crowd erupts and the referee parades around another victorious Cholita wrestler.

It’s a remarkable transformation for these women who were recently ridiculed in Bolivian mainstream society. Just a few years ago the Cholitas wouldn't be seen working in respectable positions, such as a bank or clerical job. Today, that's a thing of a past and the Cholitas occupy positions of power across the country, not only in the ring. There has also been a spate of new legislation to improve the rights of indigenous groups in recent years, including those to combat domestic violence.

It’s a long road to equality in the country, but having a visible symbol of female power in Bolivia in the form of the Cholita wrestlers is helping grapple stereotypes.

Matches are a mix of acrobatics and comedy routines.

Getting ready for the main event.

A Cholita wins her bout.

Crowd participation is not optional.

Scotsman Rob Bain is an Australian-based freelance photo-journalist whose work can be seen here.

FEATURES

THE HUMAN STATUES OF MANDALAY

In Mandalay, Myanmar the dust-covered faces of the Kyauk Sit Tan carvers draw just as much attention these days as the majestic Buddha statues they bring to life. Our feature spending the day the some of Asia's most renowned stone carvers.

FEATURE Nº10

Hundreds of men, women and children covered in white dust occupy a small lane in Mandalay each day.

By Fraser Morton

& Eszter Papp

If you catch them sleeping they look like stone, until their eyes blink open and the Kyauk Sit Tan carvers go back to work.

In a city that throbs with artisans who are experts in gold-leafing, woodwork and textiles, one little lane in Mandalay, the former royal capital of Myanmar, is filled with Burmese men, women and children who are renowned for their skill in sculpting.

The carvers of Kyauk Sit Tan have been here since the 18th century, with generation after generation learning to carve, sand and polish marble and stone into the figure of Buddha.

Few masks are worn by the carvers on Kyauk Sit Tan.

The Buddha statues made here are shipped across Asia, Europe, the United States and beyond for religious and decorative purposes.

Yin Yin Htwe says she has never thought of doing anything else. "Stone carving is a business handed down to me by my ancestors," she says. "I have been doing this job now for 40 years. I hope to pass on my business to my children too."

Finished Buddha statues, highly soughtafter and shipped worldwide.

A young carver takes a rest in the shade from the searing midday heat.

"I gain merit as a Buddhist, but this is also my business. Having this business makes me feel delighted, and I want to say ‘Well done’ to my customers for showing their faith and respect for religion."

Many of the workshops here have been handed down four generations. At most workshops the entire family pitches in: The men hammer and lift heavy stone while women and children add intricate detail. Everywhere there is dust. It clings to hair, eyelashes, nostrils, hands, shops and cars and hangs low in the tropical heat. It’s a compelling scene that is drawing travellers. They come to see the carvers and their craft, which has been set in stone for centuries here in a little lane in Mandalay.

Today, power tools have replaced crude carving instruments.

Teenage stone carver.

Portrait of a carver.

Thousands of statues line the lane.

One of hundreds of stone carvers on Kyauk Sit Tan.

Some statues arrive at Kyauk Sit Tan with only heads to be finished by the skilled carvers along this little lane.

As seen on Ozy.com

FEATURES

THE MASKED MEN OF BALI

Our documentary portrait of a mask dancer and carver keeping alive his artisan culture in Mas, Bali. "Culture is the foundation of your life. It's like if you build a house, If you have strong foundations, your house will stay strong."

FEATURE Nº9

By Fraser Morton

& Eszter Papp

Masked performances have featured in Balinese life for 1,000 years and depict human, animal and mythological characters from Hindu philosophy.

Anom is a renowned dancer of the topeng pajegan, a one-man show in which he embodies multiple characters. “A mask dancer in Bali, this is like a storyteller,” he explains. “Because a long time ago in Bali, we have no TV, we have no newspapers, we have no internet.” Anom says mask dancing was their form of media to tell people about social life, about religion, about Balinese culture

Mask dancer Anom with his wife at his home in Mas, Bali.

“I have to talk with the spirits also. And chat with the spirit. The spirit who is the god of the mask,” Anom says. “I invite them to come, to help me, to guide me. I am thinking about the story, what I am supposed to say. Who I am. I am in every single character. I forget everything. My problems. Sometimes I forget my wife and my kid. I am focused on what I am doing at that time. I have to focus. Like my elders said, if you want to be a mask dancer, the least you must do is portray the character of the mask. That is what it means to be a mask dancer.”

Anom hands out offerings during his performance.

Anom preparing for a local temple show.

He continues: “Culture is the foundation of your life. It is like if you build a house, if you have strong foundations, your house will stay strong.”

Topeng dancers must have detailed knowledge of Gamelan music and be fluent in seven Indonesian languages.

Today, Anom travels the world educating people about Balinese culture. He is also teaching his son mask dancing — ensuring a fourth generation of his family heritage.

“I am worried a little bit,” he admits. “But I have hope in the young generation. Many young Balinese people go to work on cruise ships. They work for a few months, a few years. They learn another language, they learn another culture. But even when they are far away, they still remember where they come from.”

Mask performances take place at 20,000 Hindu temples in Bali. They also feature in the Kecak, a dance made popular by tourism and performed nightly at Uluwatu.

Anom, who plays many characters each night, says with pride, “I keep alive my culture.”

The Kecak fire dance at Uluwatu Temple.

As seen on Ozy.com

FEATURES

FACES OF MYANMAR

Our 2017 travel photo essay from Myanmar through the people we met along the way. In a country awakening to tourism we found struggles, artists and characters at every turn.

FEATURE Nº8

PORTRAITS OF A COUNTRY AWAKENING TO TOURISM IN 2017

Bagan - Mandalay - Loikaw - Taungoo - Yangon

By Eszter Papp &

Fraser Morton

A little girl dressed in celebratory dress rides a buffalo with her family to the village temple. We managed to get an invite to a shinbyu ceremony, the initiation for young children entering monkhood. In Myanmar children as young as 18 months take part, and today the whole village turned out to mark the occasion, located down a dusty path in farmlands about 20 kilometres outside Bagan.

We met her at the Mandalay Jade Market. She asked us where we were from. She liked our T-shirt, we liked her smile.

He was helping his mother wrap beetle nut quids at the Mandalay Jade Market. He told us he liked this photo of himself the best.

Burmese women ride atop a truck on the outskirts of Loikaw after a hard day's work laying a new road.

We met her on Kyauk Sit Tan, Mandalay's famed stone carving district. She was collecting donations for the nunnery.

We saw children wearing these little hats in Mandalay, Yangon and Bagan.

Loikaw

Bagan

The longneck grandmothers of Loikaw.

Future of Myanmar. Dalat Ferry, Yangon.

Attitude. Dalat Ferry, Yangon.

Shwedagon Pagoda, Yangon, Myanmar.

Shwe Hile village on the outskirts of Bagan.

Bago Snake Temple

Mandalay at dusk down by the U Bein Bridge.

She asked to take our photograph with her friends while we were taking in the view at a dam just outside Loikaw. They were dressed in traditional tribal wear from the various states of Myanmar. They were on their way to a festival of diversity, she said. He friends wanted to take our photo. Of course, we had to oblige.

A very happy sister and brother duo outside of their e-bike rental store in Bagan.

Shinbyu ceremony, Shwe Hile village.

Entering the monkhood.

On his way to have his head shaved and enter the monkhood. Shwe Hile village.

Little nuns walk around the Mandalay Jade Market asking for donations.

Sharing is caring. Lunch for the nuns at the Mandalay Jade Market.

Watching his friends ride past on buffaloes at a shinbyu ceremony in Shwe Hile village.

Women do the bulk of the manual labour in the village of Pan San, Loi Kaw, including cotton farming, which the longneck tribeswomen the village is known for use to make their handicrafts, scarves and clothes.

Child stone carver, Mandalay.

Covered in stone dust, Mandalay.

The morning balloons about to take flight over Bagan.

A Chinese buyer inspects the quality of Jade from a Burmese supplier at the Mandalay Jade Market.

At an abondoned theme park in Yangon, a man watches his friends play chinlone.

Little monks take a stroll in the park. Yangon.

A lovely lady in Bagan.

See more of our travel & documentary photography here.

---

Go further.

Reach out below.

Let's start the journey.

FF

FEATURES

FINAL ACT OF THE STILT FISHERMEN

Where tradition plays a part in tourism. We meet the last men behind Sri Lanka's iconic image.

FEATURE Nº7

THE LAST MEN BEHIND SRI LANKA's ICONIC IMAGE

Two of Sri Lanka’s last stilt fishermen. Photo by Fraser Morton 2017

A man fishes from a wooden crucifix a few metres above crashing waves that fizzle out on the shoreline. The scene could be a hundred years ago. On his head he wears a turban. No shirt or shoes, only a ragged sarong. He looks a picture of tradition, a spitting image of the men who coined the style of fishing after World War II.

Despite the appearance there are no fish being caught. A few rupees from tourists are the only thing being reeled in. The tradition of stilt fishing is no more. Except, maybe, for Samaat and his friend.

He's not easy to find. But a few kilometres along the coast from Mirissa at Weligama we find him on his fishing perch. He is not a picture of tradition. He wears sports shorts and a rash guard, a gift from his son who runs a local surf school. Samaat says that he and his friend are the last men in the area who still use the style of fishing.

"Each night I go out. I go to my perch (petta). My one is that one over there," he says pointing to the farthest wooden crucifix, about five metres out to sea.

"We fish like this for fun," he says, smiling. "To relax. Why else would anyone fish this way these days?"

A fishermen poses for tourist photos.

The style of fishing is crude and inefficient. It was originally coined following World War II, when limited food and fishing areas prompted some men to innovate. Today, however, while many of the pettas remain rooted in the sand, the fishermen have gone to sea. Entering the more lucrative deep-sea fishing industry, or working on whale watching tours.

It was American photographer Steve McCurry who brought the stilt fishermen to the world's attention with his 1995 series, creating iconic images that travellers to this day come in search of.

Samaat says it's only a matter of time until the tradition dies out.