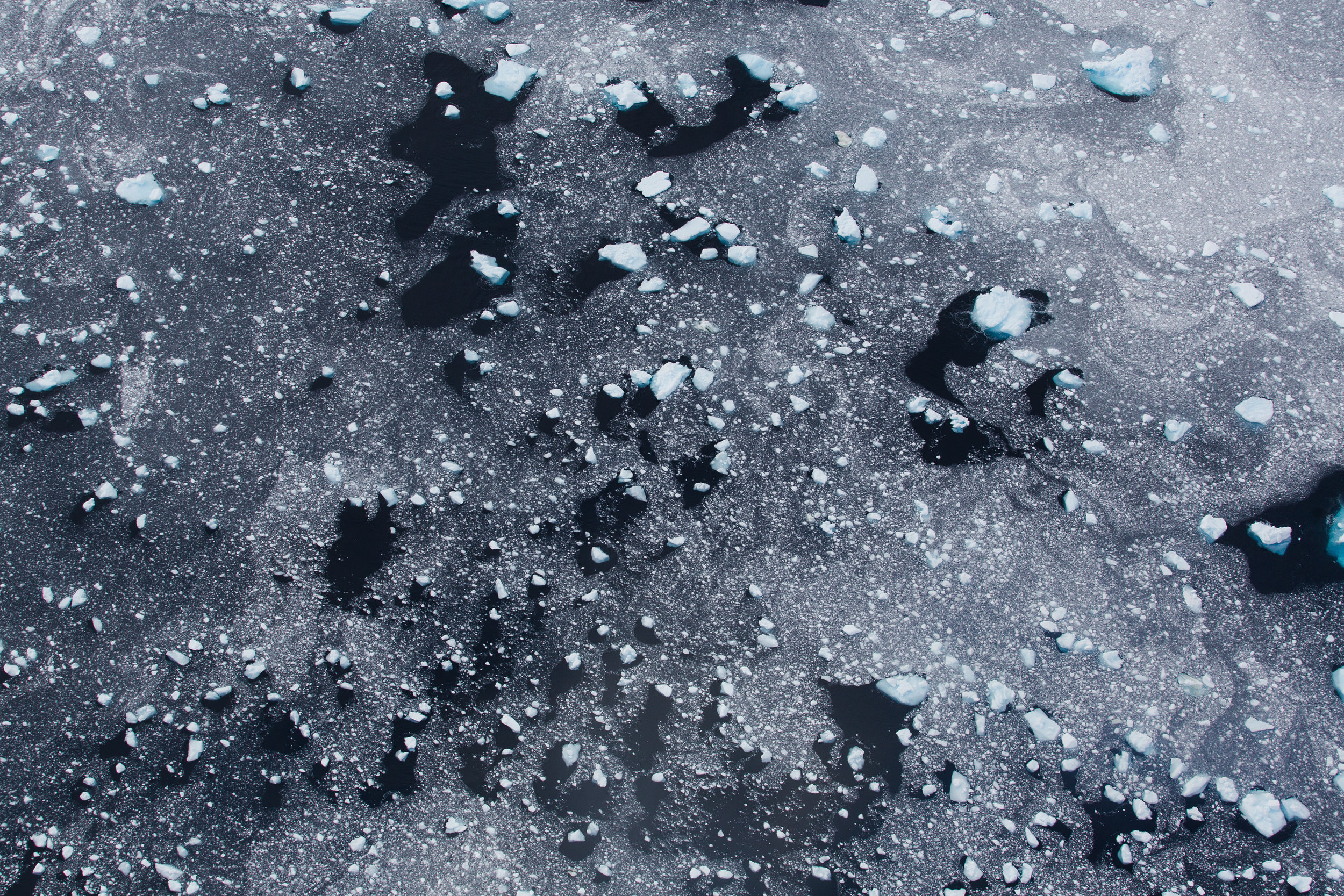

Written in the ice,

there are STORIES

CRYOSPHERE CHRONICLES IS AN ONGOING DOCUMENTATION OF ICE IN WORDS, FILM & PHOTOGRAPHY.

AN ARTS EXPLORATION OF OUR RELATIONSHIP WITH THE CRYOSPHERE.

What's the cryosphere?

The cryosphere is the part of the Earth‘s climate system that includes solid precipitation, snow, sea ice, lake and river ice, icebergs, glaciers and ice caps, ice sheets, ice shelves, permafrost, and seasonally frozen ground. The term “cryosphere” traces its origins to the Greek word ‘kryos’ for frost or ice cold. - WMO

(2018-ONGOING)

If your organisation is interested in partnering,

exhibiting, screening or distributing this project, please enquire below.

POLAR PODCAST

#4 — DIARY OF A VOYAGE HOME TO A CHANGED WORLD

This is the diary of a voyage home to a changed world by Antarctic team leader, documentary photographer and former Sea Shepherd cameraman, Sam Edmonds. As the COVID-19 pandemic spread around the world, the Australian boarded one of the last tourist cruise ships to head south for the season. The Ocean Atlantic eased out from South America when there was a mere 2,000 cases of the virus worldwide, but returned with its crew and 200 passengers to humanity completely changed. Subscribe, share and if you like this episode, please rate it www.ratethispodcast.com/twopoles. Follow @two_poles (INST) @farfeatures (FB) www.farfeatures.com/twopoles & support https://www.patreon.com/farfeatures

This is the diary of a voyage home to a changed world by Antarctic team leader, documentary photographer and former Sea Shepherd cameraman, Sam Edmonds. As the COVID-19 pandemic spread around the world, the Australian boarded one of the last tourist cruise ships to head south for the season. The Ocean Atlantic eased out from South America when there was a mere 2,000 cases of the virus worldwide, but returned with its crew and 200 passengers to humanity completely changed. In this episode, Edmonds reflects on his experience arriving back to civilisation from the seventh continent during a crisis, and the wider implications for Antarctic tourism post-pandemic.

Subscribe, share and if you like this episode, please rate it www.ratethispodcast.com/twopoles. Follow @two_poles (INST) @farfeatures (FB) www.farfeatures.com/twopoles & support https://www.patreon.com/farfeatures

Expedition team leader and documentary photographer Sam Edmonds recounts his journey to re-enter civilisation after being locked out at sea aboard Antarctic cruise ship The Ocean Atlantic.

Words by Fraser Morton

Photography by Sam Edmonds

On February 29, 2020, when Sam Edmonds was dropped off at Sydney Airport by his girlfriend, it was supposed to be a routine three-week trip to Antarctica. Little did he know, he was about to embark on a seven-week odyssey and return to a world completely changed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

As he flew out to Santiago, Chile, and then onto Ushuaia, Argentina, the new virus COVID-19 was in its infancy with less than 2,000 cases worldwide and zero deaths in Australia. It would be two weeks before a pandemic was announced by The World Health Organization (WHO). By that time, Edmonds would be on a ship somewhere off the coast of Antarctica.

He was embarking on a voyage that he had made many times. For the past seven years, Edmonds has worked in polar regions’ tourism industry as a guide, photographer and team leader. Previously, he was a cameraman for Sea Shepherd, documenting anti-whaling missions in the Southern Ocean off Antarctica and illegal fishing operations in the Gulf of Guinea.

Despite being used to at-sea drama, this voyage would turn into one where Edmonds would experience an unprecedented series of events, hazards and biosecurity measures that today look set to have a lasting effect on Antarctic tourism operations for years to come.

“The last few weeks have proven one of the biggest professional challenges I have faced,” Edmonds said.

Tourists aboard The Ocean Atlantic in Antarctica.

BEST LAID PLANS

On March 2, 2020, Edmonds recalled it was a brilliant sunny day in the port town of Ushuaia, Argentina, the world’s southernmost town and jump-off point for Antarctic cruise ships departing to the seventh continent. This would be his last voyage South for the season. The long dark winter was approaching, a time when Antarctica enters icy hibernation and no ships make the treacherous Drake Passage crossing.

As team leader, Edmonds oversaw the boarding of the 200 passengers, who had travelled from 13 nations, with the vast majority of them hailing from Australia.

For many it would be the trip of a lifetime. One of the growing number of voyages that transport approximately 56,000 tourists to visit the continent each year aboard cruise ships like the The Ocean Atlantic.

The first week in March was the last week before everything changed for the Antarctic tourism industry. And The Ocean Atlantic was one of the last ships to leave before the pandemic escalated. The following week, a few more ships would depart south, including the now well-documented, Greg Mortimer.

At that point, Edmonds said that the only sign of anything out-of-the-ordinary was that the ship doctor was taking temperature checks of passengers as they boarded.

“As we set sail, I think most passengers felt positive about heading south and leaving this new COVID-19 virus behind them.”

The Ocean Atlantic enjoyed a remarkably smooth crossing of the infamous Drake Passage, the body of water ships cross to reach Antarctica between the tip of South America and the seventh continent.

“We had Drake Lake conditions, which were very smooth, very calm water — a great way to start the trip.”

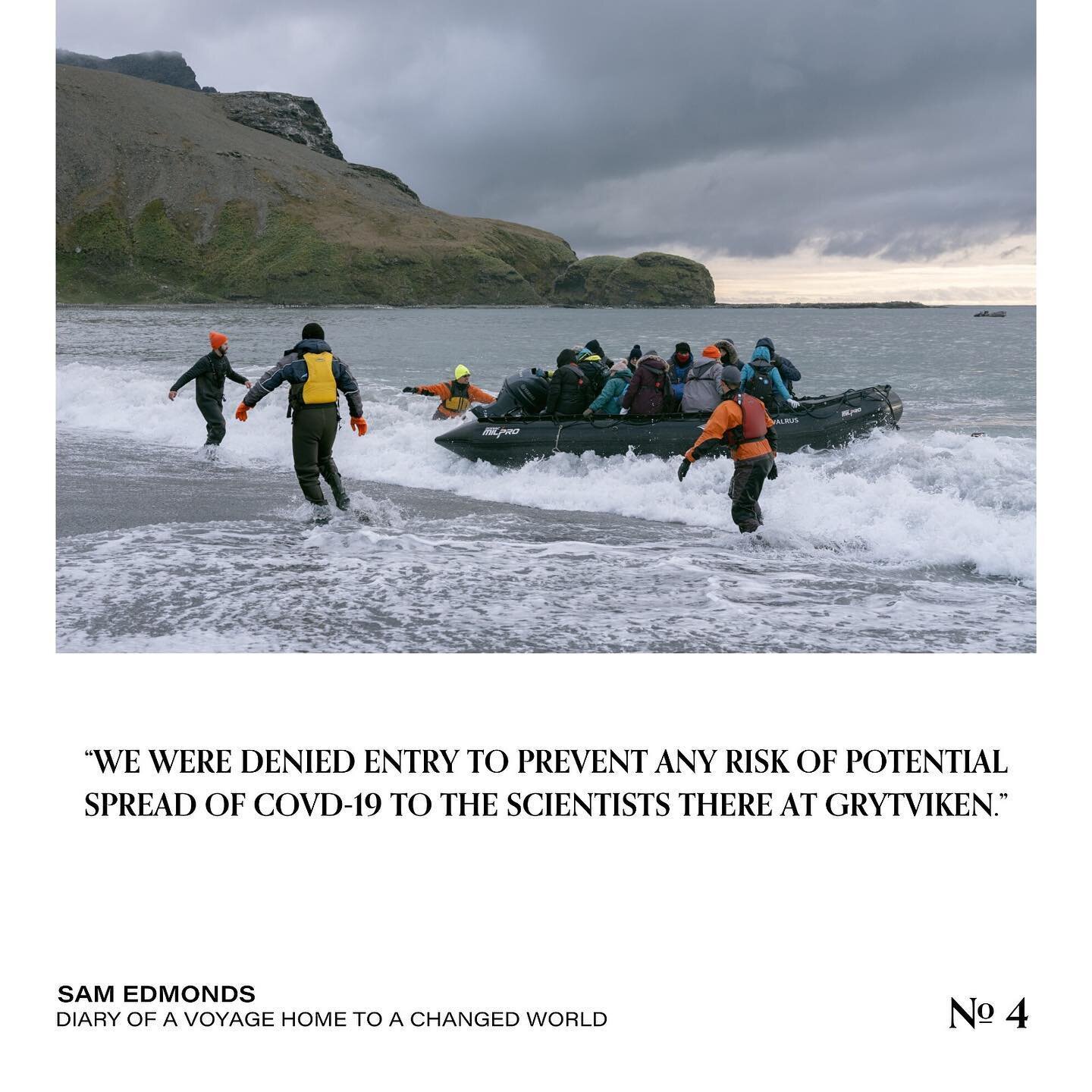

Expedition crew await the arrival of zodiac boats filled with tourists at South Georgia, Antarctica.

King Penguin colony, South Georgia.

Landing at South Georgia.

The Ocean Atlantic arrived at its first destination, the South Shetland Islands, a remote archipelago about 70 miles north of the Antarctic Peninsula, where the team made a landing on a remote beach. While there is a human population at remote research bases on the islands, the group made no human contact with any outsiders.

Next, the ship made a short crossing to the Danger Islands, a historically famous location usually difficult to access.

“Up until this point, it was one of my best Antarctic trips. We got to see some up-close leopard seal predation of penguins and the conditions were on our side.”

But as The Ocean Atlantic made its way through Antarctic Sound, katabatic winds gusting up to 50 knots swept through the bay and the decision was made to cancel a landing and visit to Argentinian Science Research Base Esperanza.

“This was the first point where it emerged COVID-19 may disrupt plans. At that point one of our Chinese guests came up to me and asked if it was really the wind, or fear over a potential COVID-19 outbreak aboard the ship reaching the scientists. He very kindly offered for the Chinese guests not to go ashore and stay on the ship if those were indeed the fears.”

But Edmonds said the decision was made due to weather conditions. And the passengers never visited the science base or made any human contact.

“That is something I have reflected on a little bit due to the events that later unfolded.”

Tourists make a landing in Antarctica.

Tourists explore the Antarctic Peninsula.

Tourists aboard The Ocean Atlantic in Antarctica.

Antarctic Peninsula.

The ship stopped off at Point Wild, where passengers saw the famous bust of Captain Luis Pardo, marking the point where Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance expedition was rescued on August 30th, 1916.

“It was at this point that we received communication of the rapidly deteriorating situation because of COVID-19 happening back home.”

On March 17, now more than two weeks into the trip, The Ocean Atlantic arrived at Grytviken, formerly the largest whaling station on South Georgia, where they received word: “Entry denied”.

“We received communications saying we were being denied entry to prevent any risk of potential spread of COVD-19 to the scientists there at Grytviken. The ramifications of one of the scientists there contracting the virus would be pretty dire. This was now at the point that we felt that COVID-19 had reached us onboard.”

Unable to visit the science research base or the graveyard at Grytviken, The Ocean Atlantic crew and passengers were permitted to make a landing on a remote area with no human contact, at the king penguin colonies of St Andrews Bay and Gold Harbour.

“This wasn’t a typical voyage anymore. This was now something we were conducting within the context of a very serious global pandemic. We now realised it was something that was touching everyone on Earth, including our expedition ship in Antarctica.”

The cancellation of the South Georgia visit would be a small taste of what was to come, and the bizarre nature of the situation Edmonds and his crew now found themselves.

“We were in the comfort and security of our ship, experiencing wildlife, embracing the elements while learning new things daily. This was all while the world around us was facing a global crisis, with situations worsening politically and socially by the hour.”

Quarantined at Montevideo.

Tourists kill time while quarantined off the coast of Montevideo.

A sketch of The Ocean Atlantic’s itinerary onboard.

The Ocean Atlantic made a course for South America and after almost a full day of sailing for Puerto Madryn, Argentina, the health crisis had worsened and port authorities denied the ship’s request to dock into port.

By this time in mid-March, ports and borders all over South America shut down.

The Ocean Atlantic then made a course for Ushuaia. At the same time, onboard Sam and the rest of the crew were communicating with the Australian authorities as well as the ship management company and their health advisers as to how best to step up precautionary measures on board. Passengers and crew were quarantined to their rooms, with excursion times to the outside decks limited to two times per day. All public areas on board were closed and a three-metre social distancing rule enforced.

The ship was re-routed again the next day to Buenos Aires and at this time quarantine restrictions tightened and outside deck-time was banned. These efforts were made to try make sure further quarantine was not enforced by border forces when the ship was eventually allowed to dock.

The Ocean Atlantic was among a handful of ships also trying to regain entry back to the world, but remained locked out at sea. The varying ships quarantined at sea, would face different demands from border forces. Some ships were sentenced to a two-week quarantine onboard while in port, others were denied entry and ordered to sail back to their countries of origin, like the Netherlands or South Africa.

And a few ships headed for Uruguay, which took a more lenient stance on the cruise ship arrivals and promised a “sanitary corridor” for passengers to be repatriated.

With all ports inaccessible, the only option was Montevideo, where a “sanitary corridor” had been established. Upon arrival, there was another queue of expedition vessels already waiting.

One of those ships was the Greg Mortimer, a vessel that would become a big part of The Ocean Atlantic’s story, and a brand new custom-built ship with unique build specialised for cruising polar waters, what Edmonds describes as “an emblem of how great Antarctic tourism industry had been”.

Buses arrive to provide a “sanitary corridor” to Montevideo Airport.

On March 17, Edmonds looked at the sat-nav in the control room to see what other vessels were doing.

“Almost all of them had turned back to South America, but there was this one ship, Greg Mortimer, which was heading south to Antarctica. I remember the expedition leader and then looking at this interface and saying to him, ‘Do they know something we don’t’. We were curious as to their situation but they were 1,000 nautical miles away.”

In a matter of days, everything would change. Greg Mortimer changed course north and headed for Uruguay and within a couple of days would be within 13 nautical miles of The Ocean Atlantic. Communications were established between the two ships and plans were made to co-charter a plane to fly passengers to Australia and New Zealand, due to the lack of commercial flights available at that point.

“But 48-to-72 hours later, we heard of a handful of fever cases onboard the Greg Mortimer,” Edmonds said.

Test kits were flown to the ship and it was confirmed that there were a number of positive COVID-19 cases onboard.

“We had to cut all plans for an evacuation with the Greg Mortimer guests.”

It would transpire that 60 per cent of all passengers and crew aboard the Greg Mortimer would contract COVID-19.

The ship was eventually allowed to dock in Uruguay with a reported 128 confirmed cases of the virus onboard. The ship was carrying 217 people, the majority of them were eventually flown home mid-April, with many more still left behind and awaiting transfers.

Passengers leave after nearly a month aboard The Ocean Atlantic.

SANITORY CORRIDOR

Aboard The Ocean Atlantic, the crew and passengers had to bide their time, and so Edmonds turned to his photography to keep busy.

“Managing 200 people on an Antarctic expedition vessel amidst a global pandemic outbreak, it was important to maintain some daily rituals and de-stressors. For me, this was keeping my camera over my shoulder and focusing at times on the group of human beings on board our vessel.”

Eventually, The Ocean Atlantic was allowed to begin offloading passengers and within three days passengers from all continents other than Australasia would be offloaded.

For the remaining 140 Australian and New Zealand passengers, they were granted access to a sanitary corridor to the airport via buses and military guard. They arrived at an empty airport and their first sights of a world completely changed.

“It was a very bizarre experience to arrive at a deserted airport and as we moved through this process it just became surreal and hammered home the severity of this COVID-19 pandemic. Up until this point we had only been surrounded by the other passengers for more than a month.”

The charter flight flew from Montevideo to Santiago, Chile and the subdued socially-distanced direct flight to Sydney where the passengers were met by a proactive borer force.

They touched down in the early hours of April 3, 2020.

“While there was applause and elation to eventually be back home, as soon as we taxied and the door opened that joy quickly faded as we all made our way to our two-week hotel isolation.”

Exhausted crew and passengers en route to Montevideo Airport.

Sam and the rest of the passengers were put into hotel rooms for their 14-day quarantine. He spent his time taking photos and documenting the experience.

On April 16, 2020, at one minute past midnight, he was allowed to leave quarantine.

“It was almost miraculous we managed to get everyone back in the timeframe we did. Everyone got home safely and not one person from our vessel had COVID-19. Ultimately this seems like one of the steepest learning curves of my life generally, but especially in the Antarctic.”

Sam documented the whole trip, his essay, which appeared in The Guardian can be viewed here.

A subdued flight home to Sydney.

TOURISM IMPACTS

It’s too early to tell what the impact of COVID-19 will mean for the Antarctic tourism industry.

Some reports already suggest a 50 per cent cancellation for the 2020 Antarctic tourism season which is due to resume in October - with a resurgence expected in 2021.

High-profile cruise ship cases will not have helped ease travellers decision to book, with what Edmonds calls the “vilification of the tourism industry” due to COVID-19 outbreaks aboard the Ruby Princess and Greg Mortimer cruise ships that were widely documented in media reports.

Edmonds is optimistic about tourism’s return to Antarctica, and also its purpose in the first place.

One debate frequently raised regarding tourism to the seventh continent, is if it should be allowed at all.

“It’s a constant dialogue about how necessary tourism is to Antarctica, a place that is virtually untouched by human beings. Like any other wilderness area on Earth, we have a strong desire to preserve these places. However, putting big red tape around the entire continent to have it out of bounds might not be the solution to protect it. I see first-hand every day, what experiencing the Antarctic can do to someone for the rest of their life. I see tourism as part of the human condition. We all have a drive to want to experience things and see things. What else do we do with our time on this planet if we are not experiencing it as much as we can and celebrating this rock that we live on.”

View Sam Edmonds photography work at samedmondsstudio.com

Polar guide Sam Edmonds in Antarctica.

ARCHIVE INTERVIEW

(2018)

A POLAR GUIDE'S PERSPECTIVE ON THE LAST GREAT WILDERNESS

Sam Edmonds is a polar photographer, guide and environmentalist.

I met Australian Sam Edmonds onboard the Ocean Endeavour in March 2018. I was there to film and photograph a documentary project for Eco-Business News with climate change activist group 2041, led by British adventurers Robert and Barney Swan.

Our first encounter was when he grabbed my arm to help me step from the ship to his zodiac, as we bobbed up and down in the Southern Ocean of Antarctica.

We got to chatting and sharing stories about work, and I quickly learnt that Sam has one of the best jobs in the world. He gets paid to go to Antarctica and the Arctic where he takes photographs of oceanscapes, wildlife and remote vistas. He has a unique insight into the polar regions that most people in the world don’t get to see.

Here, we discuss his passion for the polar regions and some issues currently facing the last great wilderness of Antarctica.

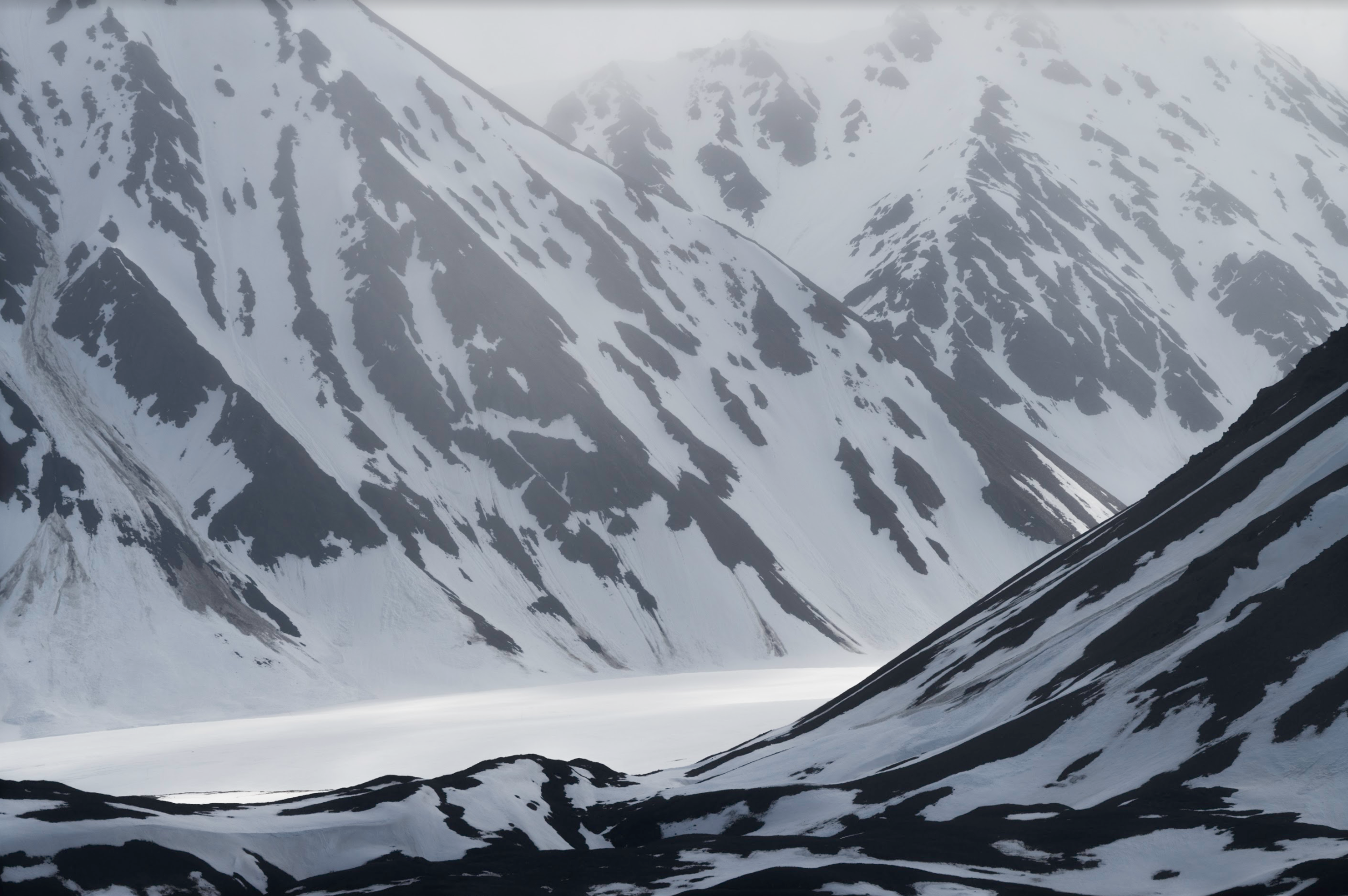

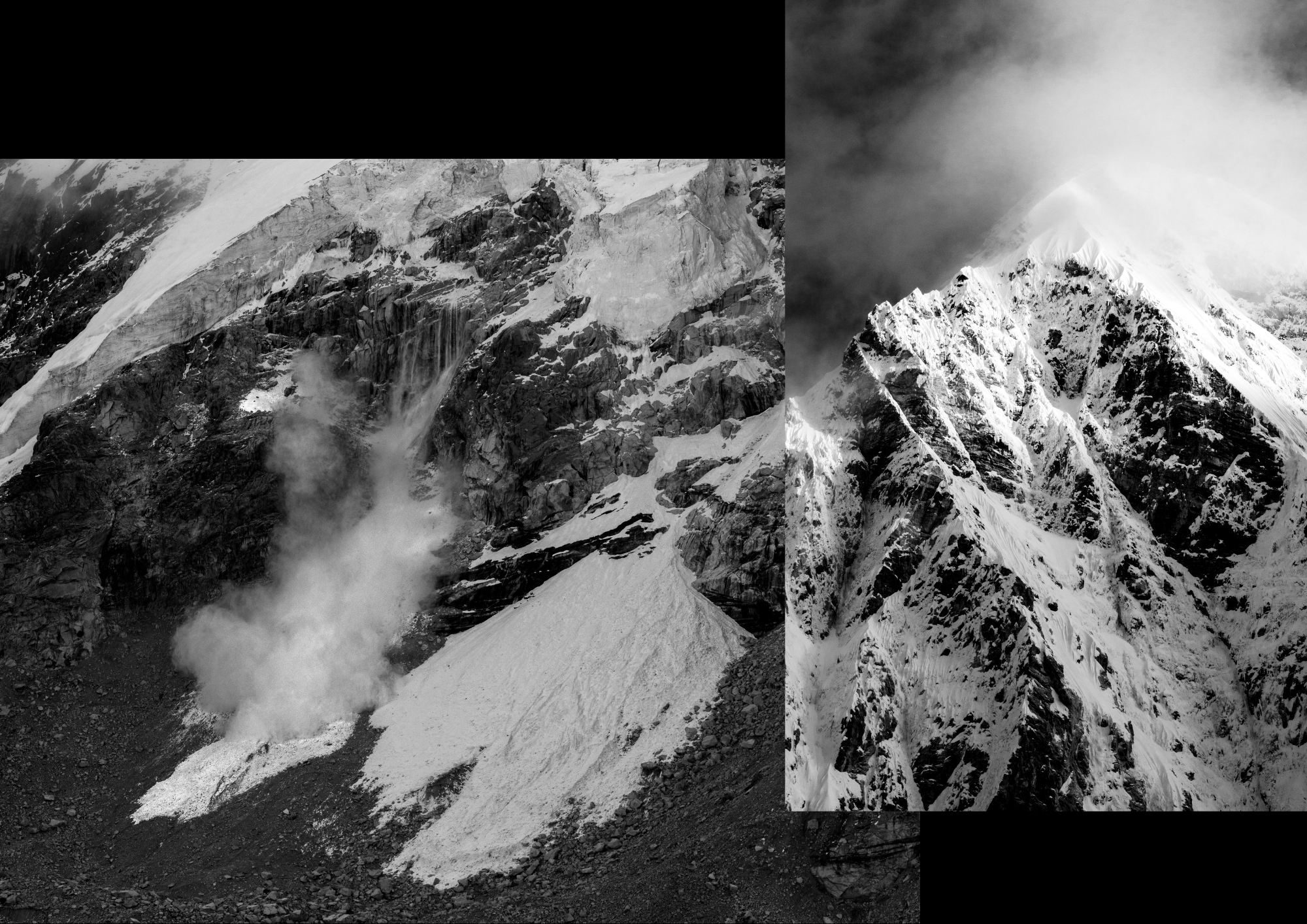

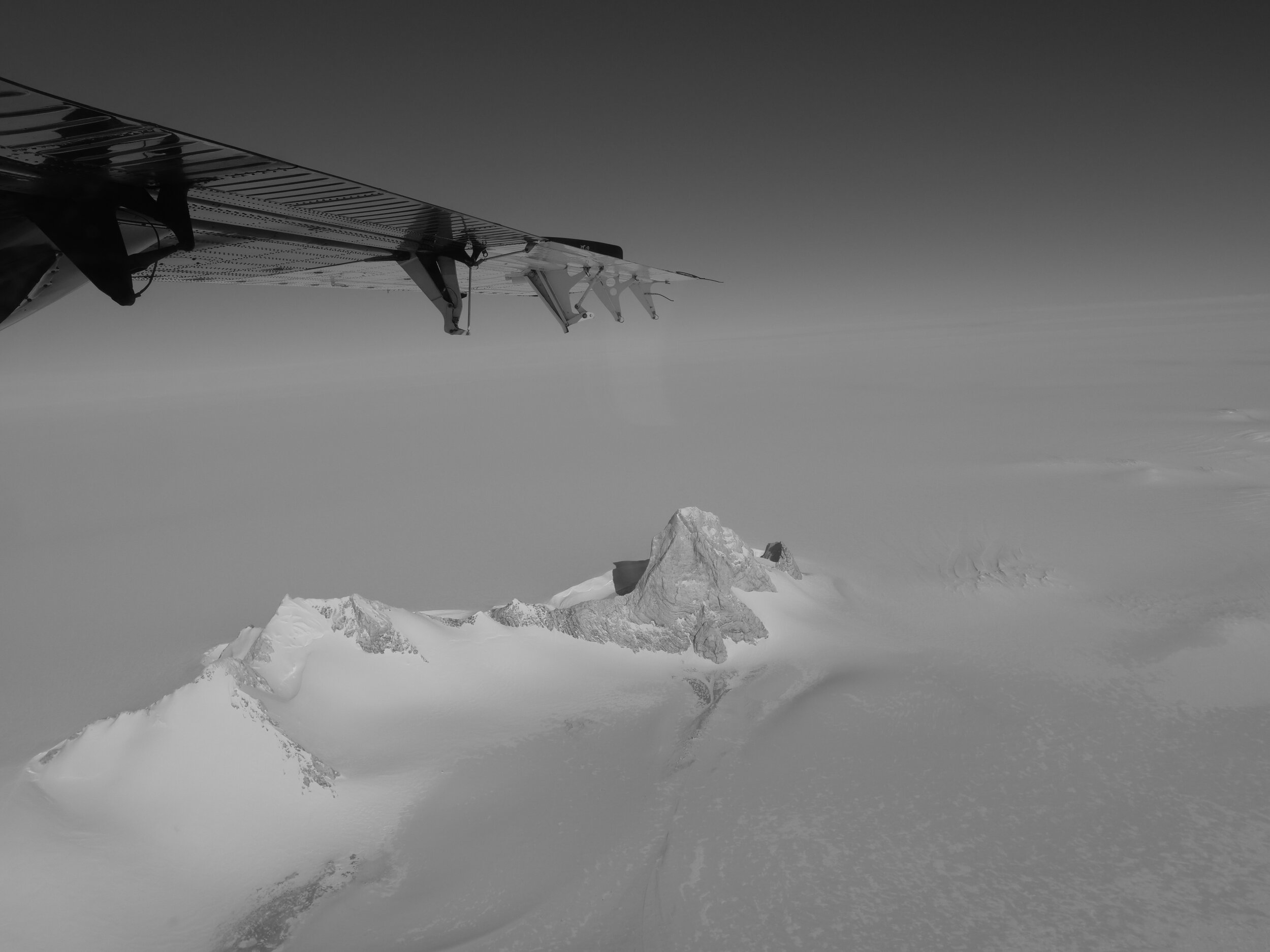

Antarctica from the air / Sam Edmonds.

FM/ How did you become a polar guide?

SE/ The idea of wilderness guiding in general seemed to make a lot of sense as a profession I would pursue as it rolls most of my skill sets into one. Also because it’s tethered to so many ideas about conservation and an almost Thoreauvian appreciation of the outdoors that I have advocated for most of my life.

How I got into guiding in a polar context really came about because I had managed to gain two seasons of experience in the Antarctic whilst filming the TV series “Whale Wars”.

ABOVE: SAM FILMED THE SERIES WHALE WARS FOR ANIMAL PLANET.

It was during that time that I obviously had the unique experience of learning about the continent first-hand, but upon reflection, was probably where I refined a lot of my “soft skills” as well: Working in a team under immense pressure, working in adverse conditions, building a rapport with people and generally being at sea for long periods of time.

FM/ What subjects are you drawn to photograph in the polar regions and why?

SE/ I often find myself in a sort of dual mode when I’m photographing in Antarctica. On the one hand, places like the Antarctic Peninsula and South Georgia afford an immense amount of wildlife photography to be undertaken, so I’m often working with that sort of visual language and in that stream of natural history documentation.

However, on the other hand, I’m also really fascinated by Antarctic tourism and how our collective perception of this ostensibly unexplored continent is being shaped by this unprecedented amount of average people that are seeing it with their own eyes for the first time.

So, most of the time I find myself switching between these two trains of thought and these two starkly different visuals languages as I explore both those themes as much as I can.

South Georgia, Antarctica / Sam Edmonds

FM/ What motivates you to keep going south to Antarctica?

SE/ I’m often asked this by guests onboard the ship, and especially when we have just come in from a very cold, wet and windy katabatibc experience somewhere! To be honest, I don’t really have an answer. I think that speaks volumes about these kind of subconscious answers that Antarctica provides for many of us as human beings.

I’ve asked almost every guest I’ve guided over the years, “Why did you come to Antarctica?”

There’s a startlingly wide spectrum of answers, but there always seems to be this theme of seeking the unknown and pushing one’s boundaries. It’s surprising how much a very cold and seemingly desolate place can seem to embrace you and offer solace.

Crabeater Seal, Paradise Harbour / Sam Edmonds

FM/ Most incredible thing you have witnessed in Antarctica?

SE/ That’s a really tough question to answer. Partly because I’ve witnessed a lot of moments of transcendence and camaraderie that were very astounding in their own right.

But most of those were as a result of immersing ourselves within the incredible Antarctic environment. However, there was one moment this most recent summer season (2017/2018) that seemed quite surreal and unprecedented.

It was in Antarctic Sound while we were transiting from East to West. A pod of killer whales was seemingly trying to isolate a fin whale calf from its parents, but at the same time a number of fur seals were swimming by and the usual suspects of sea birds were flying overhead in astounding numbers. I think we spent about four hours on the bow of ship just sprinting from port to starboard and back as all these animals surfaced and breached and frolicked right next to the boat.

I remember even some of the most experienced guides onboard were in disbelief at what they were seeing, let alone the guests who had never been to Antarctica before. So that was pretty special.

Fur Seal, Antarctica / Sam Edmonds

FM/ What worries you about Antarctica and threats to the ecosystem?

SE/ Like most places on Earth, even Antarctica hasn’t managed to escape the reach of our species as an array of threats are becoming increasingly ominous for this continent.

The impacts of anthropogenic climate change are being felt on the peninsula, but we are still yet to quantify the impacts of it locally. It will have detrimental effects on some aspects of the ecosystem but at the same time, some species like Gentoo penguins are thriving under the higher temperatures.

Personally, I’m very concerned by the exponential increase in krill fishing practices in Antarctica.

Russia, China and a number of other nations have openly expressed their intent to rely heavily on krill harvesting, which is incredibly scary. For anyone that has been to Antarctica, they have witnessed first-hand the importance of krill.

It’s the backbone of the entire ecosystem there and to exploit and tamper with that would be to pull the rug out from underneath the entire ecosystem. This needs to be addressed immediately and we will have to take a long hard look in the mirror as a species if we decide that that is a gamble we are willing to take.

Antarctica / Sam Edmonds

FM/ How do you describe Antarctica to people who have never been?

SE/ I often tell people that if they have ever wondered what the planet was like before Homosapiens, you can catch a glimpse of it in Antarctica. In many ways, I think that’s what makes this place so special. It is the world’s last remaining wilderness.

FM/ I feel like the photos I took down in Antarctica don’t do it justice one bit. Can a photograph capture the essence of Antarctica?

SE/ I’m not convinced that an image can capture the essence of anything. Photojournalism is going through some rather tough growing pains at the moment as it grapples with tearing down that precarious, false sense of “objectivity” that it advocated for so long.

And I think this is really healthy. Especially in an age where we consume to many images, yet so little of us are consciously visually literate. What I do think visual media can do for us and what applies to the polar regions is the collective voice of visual documentation that can start to shape a better understanding.

All visual crafts are inherently subjective, but as a chorus of viewpoints starts to harmonize, the power of bearing witness increases exponentially. This is when we see movements begin and things start to change.

FM/ Do you have a favourite quote you’ve read about Antarctica?

SE/

“The first great thing is to find yourself and for that you need solitude and contemplation - at least sometimes. I can tell you deliverance will not come from the rushing noisy centers of civilisation. It will come from the lonely places.”

- Nansen

---

If you like Sam's work and want to buy one of his prints,

visit samedmondsguide.com/print-store

Far Features supports independent artists we respect.

Antarctica / Sam Edmonds

If you like this story please see more of our latest Far Originals projects and support independent creative non-fiction work at www.patreon.com

#3 — WILL TO WALK: A 33-YEAR ANTARCTIC ODYSSEY

In this episode, polar activist Sir Robert Swan gives an exclusive interview about his recent Last 300 expedition to the South Pole. Hear what happened on his historic walk in what was meant to be the culmination of a 33-year odyssey to cross the entire Antarctic continent on foot. Subscribe, share and if you like this episode, please rate it www.ratethispodcast.com/twopoles. Follow @two_poles (INST) @farfeatures (FB) www.farfeatures.com/twopoles & support https://www.patreon.com/farfeatures

In this episode, polar activist Sir Robert Swan gives an exclusive interview about his recent Last 300 expedition to the South Pole. Hear what happened on his historic walk in what was meant to be the culmination of a 33-year odyssey to cross the entire Antarctic continent on foot.

Subscribe, share and if you like this episode, please post a 5* rating on Apple Podcasts or at ratethispodcast.com/twopoles.

Follow @two_poles @farfeatures & support https://www.patreon.com/farfeatures

WILL TO WALK

THE FULL STORY OF A 33-YEAR ANTARCTIC ODYSSEY

By Fraser Morton

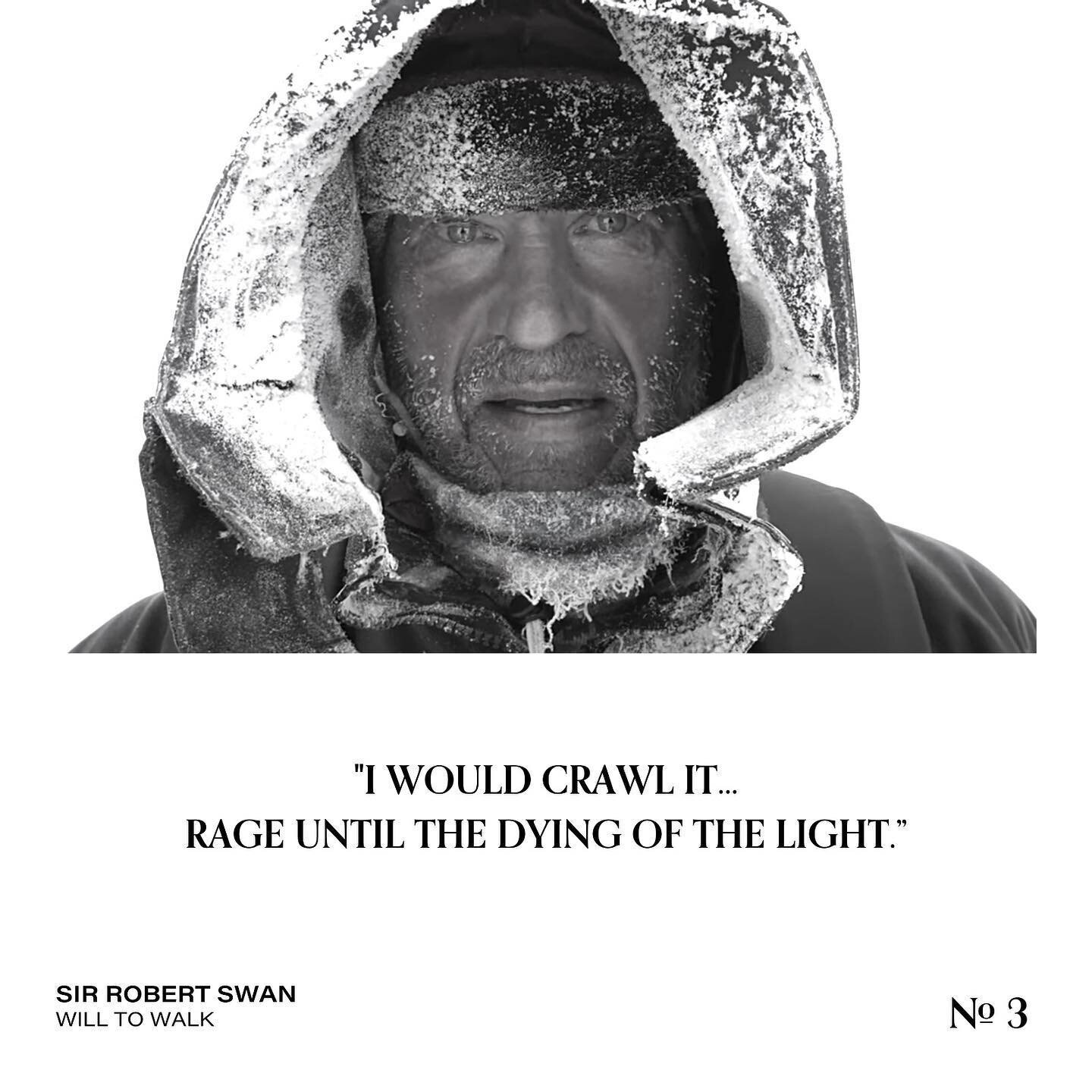

In front of him lay the first step of a 300-mile journey on foot across the barren ice desert of Antarctica. Behind him the history of his polar achievements played on his thoughts.

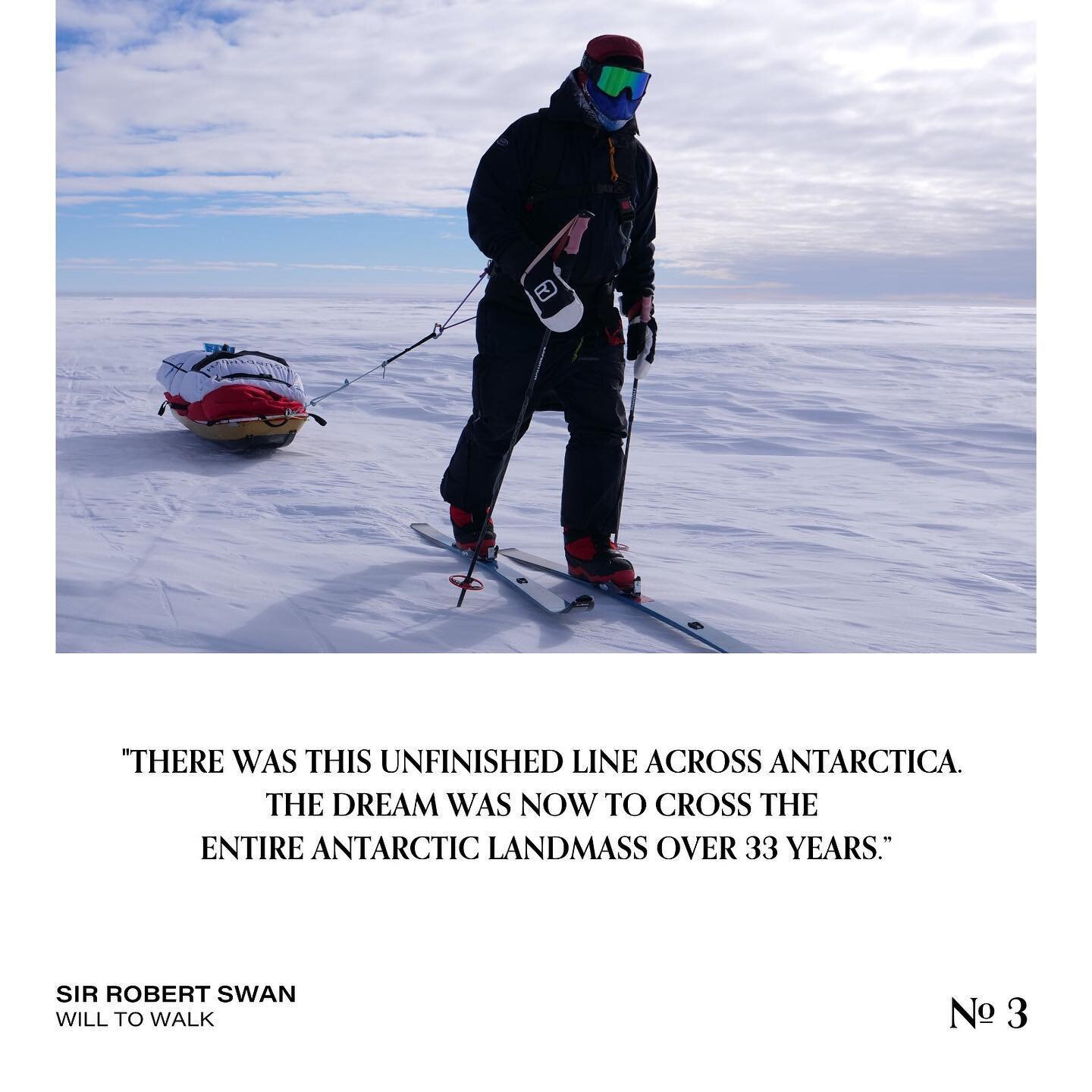

A final walk to the South Pole. His Last 300 Expedition, a fitting name for the final chapter of a 33-year trans-Antarctic landmass crossing on foot.

“Not for records, not for anyone. This one's for me. Do what you say you are going to do,” the explorer heard his own mantra.

He peered into the white abyss and felt familiar awe and dread. Not easy to describe, but inescapable in his dreams. A pull, like a magnet, sliced through the empty landscape and stabbed into him.

“I shouldn’t even be here,” he thought.

The distant call of the wild places had started in his childhood and echoed through his life as an ever-present tug at his insides. It had hardened his body, moulded his will and pushed him further than he could have imagined. The first person to walk to the South Pole (1986) and North Pole (1989). The Polar Medal. An Officer of the British Empire. A United Nations Ambassadorship for Youth. Author, speaker and mentor to thousands of environmental activists around the world. But mainly, he was a survivor of the polar places, and all because of the landscape’s silent call.

The boy had grown to become a man of achievements because of his will to face the ice frontiers. And now, as he stood with his feet in boots, clipped in skies, wrapped head-to-toe in layers of survival clothes, he peered out through masked vision upon a landscape where he would face a final test.

The first step of thousands lay ahead. As did the sound of his skis and sticks pounding snow, accompanied by the crunch, swoosh, slap, and grunts of relentless, monotonous marching while dragging his heavy sled. Exhaustion, disorientation, sleeplessness awaited somewhere out there on the ice. As did soon to be spoken “shits”, “damn its” and “bloody hells” over inevitable, tiny, errors in judgement by a soon-to-be-sleep and-oxygen-deprived-brain. Punishment awaited in frozen fingers, frostbitten toes, chaffed and bloodied thighs and absolute bone-rattling exhaustion for this 63-year-old man. He had planned for all potential pitfalls his imagination could dream up. This time, he felt prepared. His new hip had healed. He had trained for two years. He felt strong. He pushed away thoughts of agony on the ice two years ago.

“Game on,” he thought.

And then came the first step on December 2, 2019, Sir Robert Swan began what was to be his last 300-mile march to the South Pole.

Sir Robert Swan, Last 300 Expedition, Antarctica. Photo: Kyle O'Donoghue/2041 Foundation

OUT OF RETIREMENT 2019

Swan was breaking a promise to himself. This was the second time he had broken polar retirement.

“When I reached the North Pole on May 14th, 1989, I didn’t just hang up my skis. I screwed them to the wall. This was never going to happen again.”

While his 1980s expeditions etched his name in the history books alongside his heroes, the expeditions were plagued by setbacks and extreme conditions, including losing a ship after it was crushed by pack ice on the 1987 South Pole Footsteps of Scott , and almost drowning during his 1989 Icewalk due to unseasonal climactic ice melt in the Arctic Ocean.

Even taking these near misses into account, he still believes that on those occasions the landscapes “allowed him to pass”.

“Antarctica let us through and I sort of didn't really understand that at the time. Of course, we lost our ship, we had all kinds of difficulties, but Antarctica did let us through and for the North Pole, the ice cap melted months before it ever had, but again, we were let through. You can never win over these places. I was 100 per cent totally convinced that I would never do a big polar journey again.”

But 28 years later, Swan’s 24-year-old son Barney convinced his father to join him on an expedition to the pole called The South Pole Energy Challenge. The idea came after the pair visited a NASA facility and were shown a map of Antarctica highlighting the imminent threat of a break up of the massive Antarctic Larsen C ice shelf due to climate change.

“NASA was saying, no one is listening to us. We need to get people taking this seriously.”

Soon after, the younger Swan founded the Climate Force Challenge, a seven-year mission to clean up 326 million tonnes of Co2 by the year 2025 by championing clean energy use and working on clean-up missions worldwide.

To Launch Climate Force, father and son would undertake The South Pole Energy Challenge (SPEC).

And so shortly after celebrating his 61st birthday, Swan pencilled in December 2017 as the SPEC starting date – 30 years after his first successful South Pole expedition.

“The dreams of the 11-year-old in me were reborn. I felt like there was this unfinished line across Antarctica. The dream was now to cross the entire Antarctic landmass over 33 years.”

Last 300 Expedition, Antarctica. Photo: Kyle O'Donoghue/2041 Foundation

600 MILES TO GO

In December 2017, Swan senior and Barney set out in a team of four on a 600-mile march that would become the world’s first renewable-energy powered expedition to the South Pole. A feat never attempted on the North Pole, either.

NASA ice melters powered by the sun adorned their sleds, biofuels boiled their meals, and daily audio and visual broadcasts were beamed back to the world with live messages for their following fans.

They hauled sleds that weighed over 100 kilograms. As the march wore on, every muscle in Swan’s then 61-year-old body began to ache. His harness cut and chaffed, leading to bloodied skin. Frostbite set in. Gripping his ski sticks numbed his frozen hands. Barney’s toes began to rot. And what started as discomfort in Swan’s hip fast developed into long days of agony and sleepless nights under the midnight sun.

It had been thirty years to the month since he had walked to the pole, but looking around, the place hadn’t changed a bit. It was a timeless empty landscape. The only thing in sight to have aged, was him. The game had changed.

As the 2017 march wore on, Swan began to fall further behind each day. His heavy sled cut deeper into his hips. His arms ached from pounding his sticks into the snow. Everything ached and felt heavy. His mind kept racing back and forth between 1987 and 2017, step by step, decade by decade, the lines of time began to blur.

“If I had got slow 30 years ago on The Footsteps of Scott expedition, I wouldn't be talking to you now. I'd be dead, because without radio, without backup, if you got slow, you were left to die because the others couldn't help you. There was no way out. There was no communication.” As he marched on, following the ski tracks made by his teammates in front, the space between him, Barney and their other three teammates of Kyle and Martin grew further apart until they were tiny red dots on the white horizon ahead of him. He entered the “ice cell”, like some sort of ice mirage.

“When I would fall back from the team, I would see them as little red dots on the horizon. Thirty years ago, everyone wore red, and we still do today.”

Back then, he and his team were the first people to reach the Pole on foot after his heroes Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott. It had been a tough expedition, “But I had been there, done it,” Swan said.

“The older you get, the more likely you're going to get smacked by Antarctica and taught a lesson. I don't feel like I’m an old person in any way, except when I'm in Antarctica because it looks for weaknesses that you have. You might have weaknesses when you're 30, but you’ve got a hell of a lot more when you’re 60+, so this time Antarctica was looking closely at me and saying, what can we get from him? And this guy’s pretty good…maybe his knees, no, they are all right. And his back is okay, but this here, this looks interesting, maybe we can get him on the hip! It’s like a scuba diver. You go into the water in a wet suit and if it’s not done up properly, you can feel the cold water creeping in, finding something, flooding your senses with that terrible cold.”

On the morning of December 11th, Swan was losing so much time he knew the team would not be able to make their allotted distance to the Pole to stay on schedule. He skied ahead to Barney.

“Can you get there without me? he asked his son, “I can’t go on.”

“Yes, I can,” he replied.

They were 31 miles away from the midway point of their 600-mile march.

“It was the first time Antarctica really gave me a kick in the teeth. It kicked me hard and my hip disintegrated. I couldn't sleep, and the pain was immense.” Later on what was a beautiful windless day, Swan sat on the edge of his sled and watched the propeller airplane land on the snow to make the emergency airlift. Antarctica would not let him pass this time. As Swan made the short flight to the South Pole, Barney and the team continued on, finishing their march on January 15, 2018.

“That was so terrible for me because I was beaten. And it hadn’t happened before. Antarctica had slapped me in the face. It hadn't let me through. You have to realise in my head I was back 30 years before. Been there, done it – 300 miles for me wasn’t far.”

While the expedition was deemed a team success by showing that even in the harshest environment on Earth it’s possible to survive on renewable energy technology, Swan had the hard truth of accepting his own limitations.

In early 2018, he underwent a hip replacement surgery in the United Kingdom and returned to his home in California to recuperate for a few weeks before returning to Antarctica – yet again – with Barney to lead a Climate Force expedition through his 2041 Foundation with more than 100 young climate activists from 29 nations. Upon return to the USA, he felt invigorated from the voyage, and began planning another retirement vacation back to the South Pole. In big bold letters he wrote “Last 300” in December 2019 in his calendar.

With his new hip, he began his training regime: Practising yoga, dragging tyres up and down the hills in Santa Cruz, cycling over 150 miles a week as well as altitude training. During his rehabilitation, Swan drew inspiration watching tennis player Andy Murray, who had undergone hip surgery and made a dramatic comeback.

“I thought if he can pound up and down the tennis court, I can do this. If you are the first person to walk to both poles, you have the confidence to say, “I can do this again”.

OUT OF RETIREMENT — AGAIN

2019

By early 2019, Swan had assembled a team and preparations for the Last 300 expedition were gathering pace. He enlisted Swede Johanna Davidsson, a record-holder as the fastest woman to ski from the coast of Antarctica to the pole unsupported, as well as Norwegian cross-country skier, guide Kathinka Gyllenhammar and South African-Norwegian filmmaker Kyle O’Donoghue, who had marched with Barney to the South Pole on SPEC two years earlier.

Swan continued to give lectures throughout the year, travelling to 27 Nations to give motivational talks about survival, leadership and sustainability at conferences, schools, universities as he had done for the past 30 years. Every ton of carbon he produced was cleaned up by Barney’s Climate Force mission. All the while, plans for his next polar walk ticked along behind the scenes.

“While Antarctica was saying, it’s time to step back Rob, it was very hard to have been beaten after I had said to everybody that I was going to complete this journey. I ask lots of people to take small steps towards sustainability and our survival on the planet. I said I was going to do this and I’m bloody going to finish the crossing of the Antarctic landmass.”

Months of gruelling training followed. More ropes, harnesses, tyres, heat, sweat, and odd looks from morning runners as the 63-year-old dragged make-shift sleds up and down dusty Californian hill trails. His new hip grew stronger.

“Game on.”

In summer 2019, Swan voyaged to the Arctic on another of his 2041 Foundation missions aboard the National Geographic Explorer with Barney and a group of scientists, journalists, sustainability business people and youth climate activists. Little did he know, his climate change educational tour would sail through the hottest-ever summer the Arctic had experienced.

On December 2, 2019 Swan and the team boarded a prop plane at the Union Glacier base camp run by Antarctic Logistics Expeditions (ALE), they flew over the vast icescape and the route Swan had previously walked and landed at the “exact same patch of snow” where he had been airlifted out two years earlier.

The team was 300 miles out from the pole. Swan sent a short message via sat phone, which beamed their location to the GPS tracker on the 2041 Foundation website, “Landed, the journey begins!”.

His training had paid off. His hip had healed. His doctors were happy. And he felt physically and mentally ready.

“Game on.”

“I went into the Last 300 with a new attitude,” he recalled.

“I knew that I’d overcome something very important as a man to not feel embarrassed about asking other people for help. Gone was the macho man. I felt confident that this time I could say to Kathinka, Johanna and Kyle, look, I’m struggling, please take some weight without feeling like a failure. We were a team.”

The team made a steady pace over the first 100 miles amid sweltering conditions for Antarctica.

“It’s almost boring to say with these records being broken on a daily basis – but it was the hottest weather ever at 85º and 86º South. When you think of the temperatures that Scott and Shackleton had at those latitudes of -20ºC, we had -5 ºC. It’s kind of unbelievable. But while the surfaces were a bit strange, we got stuck in.”

All Swan had to do was get to 89º South, 60 miles from the pole, where his son Barney and his Last Degree expedition team of five would be waiting, and then they would all march the last 60 miles in celebration together to the pole.

“I would have completed the crossing of the Antarctic landmass and we would undertake the celebration walk. A great trip all together. That was the plan. Get to 89º South, job done.”

THE LIFE FORCE OF THE ANTARCTIC

Swan speaks of the life force of the continent. About “the lack of compassion”, of “being let through”, or like the ice itself was alive and “looking for your weaknesses”.

To describe the human-environmental relationship while crossing Antarctica’s plains he uses the analogy of high-altitude flight and the United States Airforce’s 1940s missions to break the sound barrier.

“They believed that there were demons in the sky up there. And if you tried to break Mach 1, the demons would smash you to pieces – and they did, time and time again, test pilot after test pilot, but eventually Chuck Yeager got through and broke the sound barrier. And definitely in Antarctica, when you get up there near the pole there are some pretty intense feelings that there are kind of demons there because your brain is well gone in the very high altitude. You are basically starving to death. Your body shouldn’t really be at altitude for that long so you’re struggling a bit. Antarctica in my view is alive as a force – and a force that does not have any compassion.”

Drawing parallels between Antarctica and our behaviour is a big part of Swan’s polar work, which began after he made a promise to legendary oceanographer Jacques Cousteau in 1991, “To help protect the Antarctic Treaty”.

The Treaty, signed in 1959 and coming into effect in 1961, made the continent free from nation’s interests, free of resource exploitation and as an international shared hub for science and peace. It’s regarded as one of humankind’s greatest conservation achievements. However the Treaty is up for review in 21 years, and Swan’s “2041 Foundation” intends to make sure it is once again signed and upheld for another 50 years. However, protecting the continent from human exploitation on land is one thing, but protecting from human-made heatwaves and climate change is quite another.

“Antarctica does not have compassion. I believe it’s a force – possibly the most dangerous force on Earth because if we melt it, we all swim. It’s the most dangerous latent, powerful force on the planet. We all talk about Greenland melting. We talk about the Arctic melting, but it's got nothing if the Antarctic melts and sea level rises by 500 feet – then half the planet's finished.”

ORDINAY RITUAL, EXTRAORDINARY PAIN

In extreme environments, ordinary can quickly become extraordinary. One of the less-than-documented daily routines that Antarctic explorers must face on their heroic marches to the pole is the humbling, and ordinary daily tasks, like going to the loo. Imagine for a moment, trying to relieve yourself outside with no toilet, in minus-30 temperatures, your bare bum revealed to the icy winds in climatic conditions so fierce that skin exposed for more than a few seconds can be ravaged by frostbite.

“Obviously when you go to the loo in Antarctica, you are not sitting on a lavatory seat, you go outside, minus-30, you whip your trousers down and you squat over a hole that you have dug,” Swan said.

“I know it’s difficult to imagine, but I can’t tell you how hard it is to be careful when you are getting frostbite on your private parts, your fingers, your bum – everywhere – you just want to get it over with as fast as possible.”

Each morning, like clockwork, the team took turns in going to the loo before setting off on their day’s march.

On day seven Swan was first out of his tent for the morning ritual. He dug a hole, whipped down his trousers, bent over and in that instant, “Bang, like an electric shock shooting up my leg and into my hip. It felt like somebody pulled a wine cork out the bottle, but it was inside my hip. In agony, I leant to one side and it popped back in. All I could think, ‘oh shit’”.

Shaken, he carefully walked back to the tent and told his tent mate, Kyle, “I have a problem”.

The pair hatched a plan. No hip bends — at all. Swan would have to think through every tiny muscle movement of his hip, no matter how mundane the task for the rest of the march. This was a potential expedition-stopper for Swan less than a quarter of the way into the march. He had to be extra careful, “I knew I couldn’t get distracted by the cold and had to focus on what I was doing.”

Swan and the team pressed on. Days passed of utter exhaustion and seven-hours’ marching. Weary each night, Swan sent updates via sat phone to his following fans. And as the march wore on, he had no hip issues. Morning toilet trips went by undisturbed. At night-time in the tent, he felt pinches in his hip and struggled to sleep. After 15 days, the team had only 140 miles to go.

“It was truly a wonder to be with Johanna and Kathinka, the most powerful and kind women, and Kyle always rock solid in my life, the best of tent companions.”

Each day, Swan checked his mileage and distance and felt the urge to want to press on. “But I learnt real admiration for Johanna and Kathinka, who said, ‘no Rob’, no more, get in the tent and rest because we had made our daily average.”

100 miles to go.

“I was feeling really confident. The hip was good. And I was thinking, I’ve got this, I’ve just got to be careful, and I’ll be fine.”

Swan felt waves of euphoric joy unlike anything he ever had on his 200 days of polar marches of the past.

“I took it in, I looked up, away from the skis and the next step and allowed myself to enjoy it.”

At 87º South they hit a high plateau with howling winds and miles of sastrugi, parallel wave-like ridges, which are caused by winds on the snow’s surface, notoriously difficult and dangerous to ski along with deep gullies to fall into.

On previous expeditions, Swan and the team had only encountered about 20 miles of sastrugi, but nearly 70 miles of this treacherous terrain lay in front of them. Their progress slowed and the team were engulfed by a whiteout, a weather condition where visibility drops to zero - white sky, white cloud, white snow and no shadows or contours of any discernible element of the landscape or horizon can be seen. They were marching blind. “We had a few days where we couldn’t see anything in the white out, it’s like being inside a ping pong ball. You can’t see anything. You can't even see your skis. You can't see anybody in front of you and you're stuck in this sort of white world. And I realised if I fell over badly, I’m done for.”

Swan tried in vain to take pressure off his hip by pounding his ski-sticks into the snow in an attempt to stay upright.

“I was literally walking to the pole using my arms so I didn't fall over, which took everything I had, but at the same time, as painful as it was, I was starting to think in the back of my mind, I’ve got this.”

As the team ascended to nearly 9,000 feet above sea level, temperatures plummeted to minus-30 under deceptively clear blue skies and harsh 24-hour sunlight. After battling through the sastrugi plains the team emerged incident-free.

“Still, I felt nothing. No twitch, no electric-shock-loo-moments with the hip.” The next morning, Swan woke up in his tent next to his teammate Kyle.

“He said, Rob, you know every day for 29 days you've asked me how far we are away from 89º South. I don't know what's wrong with you, but you haven't asked me this morning, so let me tell you, we are 40 miles away from Barney and the Last Degree team”

He was almost there. Swan 33-year mission: 1,460 miles total, 40 to go.

40 MILES TO GO

On the morning of Day 29, Swan unzipped his tent and stepped out onto the ice desert of Antarctica. He looked around and peered into the nothingness. A familiar cold snap rattled him, and he recorded the temperature at minus-35 degrees. He knew as they continued to rise in altitude to the South Pole, it would only get colder from here on. As he walked away from camp, his mind raced with thoughts about how close they were to the pole. And how near he was to completing his goal. It was a matter of a few miles. He could almost touch the finish line.

“And so as I go to the loo, I am not thinking about taking my time. I am thinking about how close we are to the pole,” Swan recalled.Swan whipped down his trousers, squatted, and “Bang, the hip just came out of its socket and I looked down and the whole head of the hip, the metal head was pushing out my skin. Not piercing the skin, but out of the joint. It was unbelievable pain, like an electric shock that would not let go. Normally, you touch electricity and let go right away. But it wouldn’t stop. I was lying there unable to move.”

And so a mere 40 miles to the South Pole, Swan found himself in that moment paralysed on the ice in blinding pain unlike anything he had experienced before. Within seconds the minus-35 icy chill seeped into his exposed skin and sent uncontrollable shudders through him. As he lay gasping for breath in the snow, his eyes locked on something strange across the ice desert on the white horizon. “A figure in the distance coming closer”. All he could think, “Am I dying? This is it. The bloody Grim Reaper is coming for me,” Swan recalled.

“In my head I thought I was dying, and I could feel the cold seeping into my skin. As this electric shock feeling is going through me, I look up and I see a figure walking towards our camp. We are in the middle of a continent twice the size of Australia and there's no one else here, and all I can think is, fantastic, this is it. It’s the Grim Reaper coming to collect me and I'm dying. I thought maybe I'm having a heart attack with the pain. I thought, great, I'm dead because there is a figure that we did not expect to see. You don't suddenly see somebody in the middle of Antarctica. I shouted for Kyle and he came out, took one look at my hip, and said, Rob isn't looking too good.”

Kyle helped Swan make himself decent and dressed, and got his gloves back on. Johanna and Kathinka came out and helped carry their injured teammate back to the tent.

“Meanwhile, this guy who I thought was the Grim Reaper was actually a polar explorer from Poland who hadn't seen anybody for 49 days. He had been following our tracks and walked straight into our camp. Johanna asked him if he knew how to put a hip back in its socket. He shook his head and kept right on marching. We found out he made it to the pole a few weeks later.” The team bundled Swan into his tent and assessed the damage.

“I'm lying in the tent and I know it's over. Forty miles off after all that fight. Two times knocked back. And I think to myself immediately, if I get angry and frustrated, this isn’t going to work. Right then, I said to the team, ‘we will come back and finish this’. The second thing I thought, was give me more drugs for the pain.” The team radioed ALE (Antarctic Logistics Expeditions) for an air-vac. The same prop plane arrived that dropped them off 29 days earlier with a doctor onboard who Swan knew personally. Once again, Swan made the “depressingly short flight” to the South Pole. Upon arrival, Swan was stretchered off and loaded into a tent operated by ALE .

The hip simply had to go back in. As luck would have it two doctor friends of Swan, Dr Martin and Dr Hans happened to be at the South Pole base. And so, on the tent floor a few yards away from the South Pole, the two doctors administered pain medications, letting the drugs take effect, before pushing down on Swan’s out-of-socket hip in an effort to pop it back in.

“They had to stretch the muscles out and then, it just made a pop noise, one bang and back in. And I sort of woke up and asked for more drugs, and they said, ‘No, no’ Rob the hip is back in. You’re okay! Good guys,” Swan said. In the morning, still in pain, Swan asked ALE doctors if he could be flown back to his teammates to finish the 40 miles, but they quite rightly refused and instead he was flown out, with the worst moment to fly directly over his teammates.

“Simply awful, Swan recalls. “I wept tears of failure again.” “Kyle, Johanna and Kathinka would continue to 89º South to meet the Last Degree and then carry on to the South Pole.” Swan was flown back to the Union Glacier base camp where he met Barney and his Last Degree team who were preparing to fly to meet him at 89º South. It was a bitter disappointment as Swan senior watched his son’s team depart.

On the Last Degree team were Paulina Villalonga, a 19-year-old Student from UC Berkeley USA, Rob Miller, an entrepreneur from Chicago USA, Mary Nicholson, head of sustainability for Macquarie Bank, Ian Milbourn, an investor with Notion UK, John Foster, CEO of South West Gen USA, and USA war veteran Cameron Kerr, who had one leg, the other was lost in war.

Swan found out later that Kerr had travelled to Antarctica with none other than a little upturned bucket with a small loo seat on top.

“Had I taken one of those, we may be telling a very different story right now.”

Despite his personal disappointment, his son Barney stepped up and pulled off a successful march with the Last Degree team reaching the South Pole on January 13th 2020.

“That’s twice now he’s made it to the South Pole without his Dad. Pretty remarkable. And I think that's a huge message of hope for the younger generation and leadership on his part. That is a huge message for our survival on this planet. It has to be that we work together as generations because if we don't, we're screwed.”

Always the optimist, Swan is quick to point out the correlation between his own personal setback and the achievements of the other two teams, the Last Degree and remaining Last 300 team.

“It’s not all about Rob’s hip blowing out. This is something to learn in life, that when shit hits the fan in your own life, it’s important to keep the story going for others.”

A few days later, he arrived home to California on crutches.

“I was never disappointed until I got back home and I saw the piles of paperwork that it took me to make the expedition happen, all the boxes of equipment, and suddenly I thought, ‘My God, what an effort it took.’

OUT OF RETIREMENT — YET AGAIN

2021‘THE LAST 40’

You can guess what’s coming. In December 2021 Swan plans to return to the South Pole.

“All of us suffer injuries. All of us are told that we must do certain amounts of rehabilitation. And often we do it, but we don't do it for long enough. And I think that fundamentally I could have made the tissues and everything stronger so the hip couldn't have popped out as it did. I’m focused on making it stronger. I’m focused on saying I'll go in December, 2021 with Barney and we're going to knock it off and we're going to hope that Antarctica after smashing me back twice, will let me through to finish the job.” Swan’s walking tales now are intrinsically linked to his with 2041 Foundation and in support of Barney’s Climate Force Challenge.

“I think it's important when people say they are going to do something, they do it.” As a UN goodwill ambassador and climate change campaigner for the past 30 years, he has spearheaded hundreds of clean-ups, eco-sails around the world, education programmes, established education and clean energy hubs in countries worldwide. Young people, especially, are his audience and he challenges them through his 2041 Foundation to become sustainable business entrepreneurs.

“Every day, I ask people to do their bit for sustainability. I think it’s a good example if I do what I say I am going to do on my part.”

In 2021, Swan will be 65 when he plans his Last 40 with Barney and Paulina. “I’m still in the ring. I'm not going to give up. This may be the slowest walk across the continent of all time – 33 years, but I’m not in this for records. I’ve done that. This is personal and it’s to do what I said I am going to do.”

Swan plans to use his Last 40 to draw more attention to the plight of the polar regions and raise awareness for climate action worldwide.

“It's for me. And part of it is to close the circle on what I've spent my life doing. You know we all have dreams, and as you get into your 60s I think the message is don’t forget these dreams you had when you were a kid.”

One of Swan’s mantras for people who visit Antarctica is, “From now on, whenever you look at a map your eyes will go south to Antarctica”, and the same is true for him. In his study, he has a big map of the continent with lines drawn on it, scribbles of his expeditions. The 900 miles from the 1980s. The 300 in 2017. Now the 260 miles in 2019. He looked at the tiny space on the map – a matter of inches.

“I can’t leave it alone, with just 40 more to go, can I?

In a small way, I hope my walks might be inspirational to people to not let go of dreams. No one's ever walked to the South pole with an artificial hip. I'm sure people would say, ‘Rob, you've done enough. There's no need. You proved your point. We're not going to be truly inspired by you going to finish off 40 miles’. But you know, I'm not that sort of person. When I am lying in my bed as an old man I just want to think, sure, it was a bit of a struggle getting knocked back twice – but I finished the job.”

And if there was only one mile to go, would he still go back?

“Yeah, I would crawl it,” he said, “Rage until the dying of the light.”

All images copyright 2041 Foundation

#2 — ANTARCTICA LOCKS DOWN

In this episode, we hear once again from Matthew Phillips of the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), who has been turned around from his journey south to Antarctica due to fears over COVID-19 reaching the seventh continent. Antarctica has officially locked down for winter with extreme measures taken to keep Antarctica as the last continent on Earth where the virus has not reached. Subscribe, share and if you like this episode, please post a 5* rating on Apple Podcasts or at ratethispodcast.com/twopoles. Follow @two_poles (INST) @farfeatures (FB) www.farfeatures.com/twopoles & support https://www.patreon.com/farfeatures

In this episode, we hear once again from Matthew Phillips of the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), who has been turned around from his journey south to Antarctica due to fears over the COVID-19 reaching the seventh continent. Antarctica has officially locked down for winter with extreme measures being taken to keep the virus out. We heard from Matthew in Episode 1 when he was in self-isolation in the Falkland Islands, before preparing to head South for the long winter season. He was due to take up his post as the Winter Manager at Rothera Research Station in the Antarctic Peninsula along with a team of “winterers”, who look after the remote base during sub-zero temperatures and months of darkness from March to October. But all did not go to plan. We find out what happened next.

Subscribe, share and if you like this episode, please post a 5* rating on Apple Podcasts or at ratethispodcast.com/twopoles.

Follow @two_poles @farfeatures & support https://www.patreon.com/farfeatures

EPISODE NOTES

• Antarctic turnaround

• A lonely journey home during lockdown

• Antarctica locks down for winter season

• Disruptions to decades-long science studies?

• Specialists at Plan B

• Antarctic climate science post-pandemic

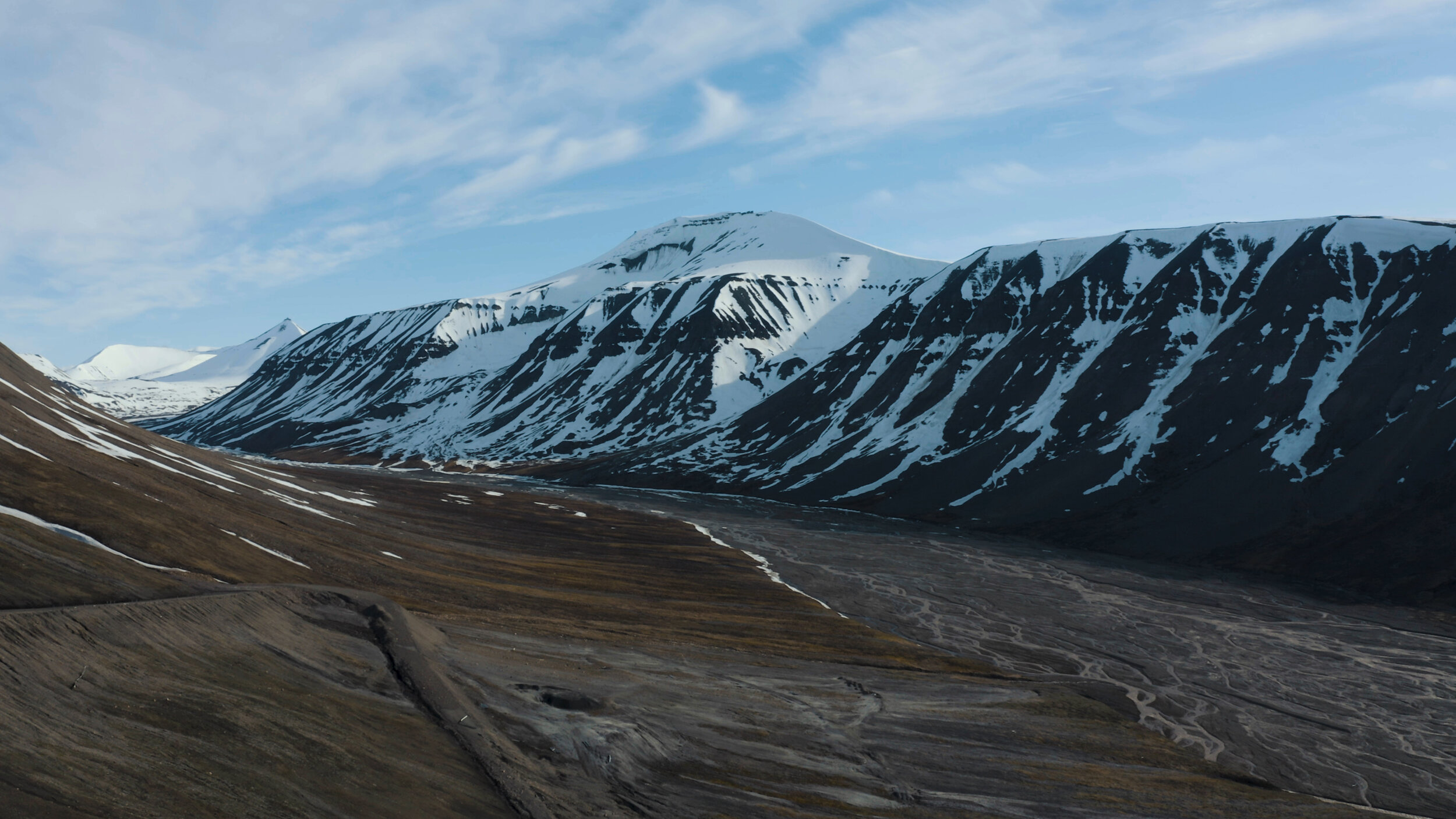

South Georgia by Matthew Phillips Photography

ANTARCTICA LOCKS DOWN

As COVID-19 continues to surge across the world, Antarctica remains the only virus-free continent on Earth. But what does this mean for the climate science research community?

All claimant nations of Antarctic territories have now reported cases of COVID-19 within their homelands: Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway, and the United Kingdom.

The Antarctic human populace is made up of scientific research staff working on bases spread throughout the autonomous region, which is owned by no single nation and governed by the Antarctic Treaty.

“Special measures have been taken to ensure COVID-19 does not reach the continent,” said Matthew Phillips, who works as the Winter Station Manager at Rothera Research Station for the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

Six months after first being detected in Wuhan, COVID-19 has infected nearly four million people and killed more than 280,000, but Antarctica is currently virus-free. However, science research personnel have been affected. Matthew is one of them. He was due to be on the last people to travel south for the long winter season in April, however, he has since been turned back home.

In April, he was in self-isolation in the Falklands Islands when news broke of the first case on the remote British outpost, which is also used as a jump-off point for many research base staff en route down to Antarctica.

In following days in late April, Matthew began the long journey back home to Scotland. He and his pilot flew a BAS aircraft to Senegal and then onto the United Kingdom. They hired a car and made the lonely drive along deserted motorways to Matthew’s final destination of Fort William.

Meanwhile, winter is coming to the seventh continent. The long dark season approaches, and the last airplanes and supply ships depart, leaving BAS winterers cut off from the world.

But what effect will COVID-19 have on Antarctic climate science?

“There won’t be any loss from our base at Rothera for this year, but looking ahead to 2021 there may be a knock-on effect. It’s too early to tell. Compromises may have to be made next summer season depending on what happens back in the UK controlling the virus and how that affects decisions that need to be made with operations down in Antartica.”

BAS issued a media statement May 1, bolstering its Antarctic COVID-19 response.

“Every Antarctic research operator is facing these same challenges. The safety of our staff and keeping COVID-19 out of Antarctica are our top priorities. Working in Antarctica is always challenging and we are used to being flexible and adaptable. That said, the whole world faces the most extraordinary challenge. Every day our knowledge of this virus changes and we don’t know how things will progress. The Antarctic research community is resilient and I know that everyone will do their best to maintain, as much as is possible, our critically important operations and science programmes,” Director of BAS, Professor Dame Jane Francis said.

“Halley and Signy Research Stations have already closed for the Antarctic winter in April. The last of the BAS aircraft has left Antarctica. Winter operations have begun at Rothera, Bird Island and King Edward Point Research Stations. These stations are currently clear of COVID-19. BAS have also updated their 2020/2021 plans to ensure operations and climate science can still be carried over the next year.”

In addition, BAS reported heightened health checks for staff travelling South for next summer season with, “Robust pre-deployment health screening protocols” in order to “avoid exposing over-wintering staff to the virus when the summer teams arrive at stations”.

Additional new measures will include: “Pre-screening, testing and stringent isolation measures for incoming staff. In addition...we will review and minimise where possible negative impact on science, construction, and future operations, with particular emphasis on avoiding irreversible damage to science or operational infrastructure.”

In recent days, the media department at BAS has been flooded with enquiries as the eyes turn to the last continent on Earth where the virus has yet to reach.

“There is a lot of interest at the moment,” Matthew said, “And that's probably largely because it's the only place that doesn't have the virus. There will be no change for our people who are already on base down in Antarctica. They will live out the winter season, which is a strange enough experience to re-enter the world after, but this time they will be coming back during a pandemic. If the UK is still in lockdown in six months, then I think people will find it interesting that there’s this group of people down in Antarctica who have been living unaffected by the virus at all. They are going to come back to find a vastly different worLd. It’s always difficult enough to come back after an Antarctic winter, never mind when the world has completely changed.”

NOTES

A full list of nations’ response to COVID-19 in Antarctica can be found at polarconnections.org.

Concerns about COVID-19 reaching Antarctica are not without precedent. In the Arctic, there has been evidence of the 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic found locked in frozen ice, and other biosecurity issues, including Anthrax poisoning found in frozen reindeer carcasses in Siberia.

In August 2016, in a remote corner of Siberian tundra called the Yamal Peninsula in the Arctic Circle.

“A 12-year-old boy died and at least twenty people were hospitalised after being infected by anthrax. The theory is that, over 75 years ago, a reindeer infected with anthrax died and its frozen carcass became trapped under a layer of frozen soil, known as permafrost. There it stayed until a heatwave in the summer of 2016, when the permafrost thawed.”

Scientists Describe How 1918 Influenza Virus Sample Was Exhumed In Alaska

SUPPORTERS

#1 — ESCAPING THE VIRUS IN ANTARCTICA

Hear what it’s like to escape humanity during a pandemic and head to the only continent on Earth where COVID-19 has yet to reach. In this launch episode, we are in conversation with Matthew Phillips, Winter Manager at Rothera Research Station for the British Antarctic Survey (BAS). Matthew is on his way south where he works in one of the world’s most remote locations. He shares his experiences surviving, living and working in the long, dark Antarctic winter season. Subscribe, share and if you like this episode, please rate it www.ratethispodcast.com/twopoles. Follow @two_poles (INST) @farfeatures (FB) www.farfeatures.com/twopoles & support https://www.patreon.com/farfeatures

Hear what it’s like to escape humanity during a pandemic and head to the only continent on Earth where COVID-19 has yet to reach. In this launch episode, we are in conversation with Matthew Phillips, Winter Manager at Rothera Research Station for the British Antarctic Survey (BAS). Matthew is on his way south where he works in one of the world’s most remote locations. He shares his experiences surviving, living and working in the long, dark Antarctic winter season. Subscribe, share and if you like this episode, please post a 5* rating on Apple Podcasts or at ratethispodcast.com/twopoles. Follow @two_poles (INST) @farfeatures (FB) www.farfeatures.com/twopoles & support https://www.patreon.com/farfeatures

PRODUCED BY

FAR FEATURES LTD

A polar podcast exploring our present and future with Antarctica and the Arctic. Armchair travel to the last great wildernesses. Journalist Fraser Morton brings you stories, encounters and wild tales from adventurers, filmmakers, writers, artists, musicians, anthropologists, scientists, and every day people who explore, work and protect these polar places. Escape humanity through polar audio stories.

Subscribe, share and if you like this episode, please post a 5* rating on Apple Podcasts or at ratethispodcast.com/twopoles.

LISTEN / SUBSCRIBE

REVIEWS

MEDIA EXPOSURE

PROJECT INTENTION

While filming a climate change documentary for Eco-Business in 2018 in Antarctica, Far Features’ Fraser Morton made a promise to polar activist Sir Robert Swan upon return home to use our work to help raise awareness of climate change-related issues affecting the polar regions. As a 2041 Foundation alumni, an NGO working to preserve the Antarctic Treaty and promote sustainability, we intend to keep our word. This new podcast aims to use storytelling as a means of connection to these last great ice wildernesses. Places of infinite wonder, power - and the fastest-warming places on Earth.

Fraser Morton. Photo by Jessica Cheam

FOLLOW

WRITE TO US

Email podcast producers

ANTARCTICA

ARCTIC

PHOTOS BY FRASER MORTON

SPONSORSHIP

We are accepting sponsorship from the right partners whose values align with our own.

Contact for more info here. Media release here

SUPPORT

If you like this new podcast and want to support, find us at www.patreon/farfeatures